This contributed piece is a part of our Featured Voices series, which invites writers, poets, artists, and creators to explore the various intersections of Blackness and Greenness. This personal essay is by Dr. Jennifer D. Roberts, a tenured Associate Professor in the Department of Kinesiology, School of Public Health at the University of Maryland College Park (UMD). This piece explores the historical legacy of racism in the context of access to green spaces. Rooted in an exploration of her own hometown of Baltimore, Dr. Roberts examines how race, class, and place have influenced the complex relationships Black folks have with nature.

Hear It? That’s the sound of rain pattering like the rhythm of African ancestors.

Smell It? That’s the fragrance of overgrown mint in grandmother’s urban garden.

Feel It? That’s the sensation of wind made from a swaying Oak tree canopy.

See It? That’s you, a reflection of Black beauty in majestic Earth’s oceanic waters.

The healing power of nature runs through Black bodies like mother’s milk to a child’s belly. Distinctively, the “unveiled face of nature,” as denoted by W.E.B Du Bois, was molded to welcome and heal the oppressed “in the tired days of life” and “renew their spirit.” Yet, American colonization, structural racism, and White supremacy stripped away and wounded the relationship between Mother Earth and generations of Black communities. Despite the oppression, traumas, and violence of being an enslaved African shipped to the “New World,” a maroon living in woods or swamps for generations, a disenfranchised sharecropper existing in Jim Crow South, or the endurer of Central Park White privilege, the natural world has always provided Black people a haven to escape the realities of bondage, brutality, and bigotry. For me, as a Black woman living in Baltimore surrounded by the realities of green space injustice, nature is, and will always be, my inspiration, my freedom, my truth.

Strange Fruit

The Reconstruction era following the American Civil War was one of the most rebellious and violent times in modern history. While efforts were directed at reunifying the South with the Union to guarantee citizenship and constitutional voting rights for Black Americans, that era primarily summoned an escalation of White supremacist terrorism and an accentuation of oppressive and discriminatory policies and practices. During that period, sharecropping became one of the most effective agricultural systems instituted in the American South. With millions of emancipated Black people needing places to live and work, sharecropping offered those resources, but placed most Black people in perpetual servitude and inhibited their prosperity. However through labor, sharecropping did maintain Black peoples’ connections to land and Mother Earth. In the 1930s, renowned 20th century author Zora Neale Hurston, published two of her classic literary works, Mules and Men and Their Eyes Were Watching God, expressing this connection as well as a deep admiration and reverence for nature. In Mules and Men, Hurston wrote, “My ole man planted cucumbers and he went along droppin’ de seeds and befo’ he could git out de way he’d have ripe cucumbers in his pockets. What is the richest land you ever seen?” “Well,” replied Joe Wiley, “my ole man had some land dat was so rich dat our mule died and we buried him down in our bottom-land and de next mornin’ he had done sprouted li’l jackasses.”

In addition to sharecropping, after the Civil War southern governments adopted “Black Codes” to curtail Black American rights and perpetuate White supremacy. Modeled after slave codes, southern legislators created Black Codes to reestablish the economic, social, and political limitations imposed by slavery on Black people. Vagrancy or appearing idle, employment regulations with stringent requirements, and penalties for violations were enacted as Black Codes. These codes resurrected the White supremacist order that served as the antebellum American bedrock and paved the way for political violence and control over the newly liberated Black Americans. With Black Codes, individuals who were often guilty of no crimes, could be convicted and sentenced to penal labor for very innocuous offenses.

As northern public opinion communicated a hypocritical outrage of Black Codes in the years following Reconstruction, many Southern states restored several Black Code provisions in the form of “Jim Crow” laws. During this time, numerous acts of violence were committed by White nationalists, including the Ku Klux Klan. Through violence, specifically by lynching, the Ku Klux Klan sought to undo the reforms brought about by Reconstruction, reclaim control of the Black American workforce, and reestablish racial allegiance in all spheres of southern society. Lynchings involved defilement, barbarity, mutilation, and concluded with Black bodies hanging aflame like “strange fruit” “from the poplar trees.” These spectacles of terror, often attended by White Americans as entertainment in celebration of White supremacy, were most commonly held in natural spaces, including parks, farms, or rivers. Unlike the rewarding natural experiences gained from farming, gardening, and cultivating sustenance from the Earth’s surface, for many Black people the lynching of Black bodies misguidedly symbolized the Earth’s betrayal and inhumanity.

Black Butterfly

Beginning in the 20th century, the Great Migration occured as a massive exodus of nearly six million Black people from the American South to northern and western cities. Over six decades, “a rural people had become urban, and a southern people had spread themselves all over the nation,” which was aptly expressed by Isabel Wilkerson in her Smithsonian Magazine article. While segregation was not legalized in the North as it was in the South, this form of oppressive separation functioned as a way of keeping Black Americans in place. Housing exemplified this form of segregation through racial covenants and government sanctioned actions, including redlining. As part of a federal government program for housing and mortgage relief “residential security maps” were created for over 200 American cities that analyzed mortgage lending risk in various neighborhoods within each city. With a scale from green (low risk; most desirable), blue, yellow, to red (high risk; least desirable), each neighborhood was graded on a set of criteria, but most importantly racial and ethnic composition. As such, areas inhabited by Black Americans or other “undesirable” ethnic groups were redlined and deemed “high risk.” Redlined homes and neighborhoods were then disinvested, resulting in reduced availability of parks, tree coverage, and other green spaces. Baltimore, my home, was one of those 200 cities.

Roland Park, a northern area of Baltimore, became one of the country’s preeminent garden communities built entirely for White residents. The park was planned by Roland Park Company and designed by land architect Frederick Law Olmsed, Jr. in 1891. With the purchase of one hundred acres situated on bucolic hills surrounded by wooded areas with mature trees and flowers planted by design, Roland Park was promoted as a clean and healthy alternative to the grit, grime, and “decaying filth” of city life. Additionally, the Roland Park Company offered a solution to quell the fears of migration, immigration, and the integration of Black and White Baltimorians. As the company became a citywide leader in selling planned communities that incorporated nature and green space, it was chiefly recognized for their exclusion of Black residents as indicated in a 1912 property deed, which stated: “At no time shall the land included in said tract or any part thereof, or any building erected thereon, be occupied by any negro or person of negro extraction. This prohibition however, is not intended to include occupancy by a negro domestic servant.”

Many Black Baltimoreans have reduced access to nature, are exposed to higher air pollution and extreme heat, and experience worse health outcomes and shorter life expectancy.

Roland Park Company leveraged the support of Baltimore Mayor, James H. Preston. Preston instructed housing inspectors to “cite anyone who rented or sold property to Black people in predominantly White areas for code violations, and the Committee on Segregation and racial covenants were sanctioned into city policy. As a result of both federal and local housing policies, the ensuing racial segregation, and pattern of discriminatory neighborhood disinvestment, a “butterfly” of Black communities fanning across the eastern and western halves of Baltimore was formed. Today, these Black neighborhoods still experience the consequences of Baltimore’s racist housing legacy. Many Black Baltimoreans have reduced access to nature, are exposed to higher air pollution and extreme heat, and experience worse health outcomes and shorter life expectancy.

White Wilderness

The social transformations of the late 19th century, specifically the emancipation of Black Americans and inflow of immigrants, initiated a crusade to preserve “American wilderness,” a classified White space. This preservation movement aimed to secure and uphold White racial identity, purity, and supremacy through the establishment of racialized spaces, like national parks. The United States National Park Service (NPS), the agency that manages all national parks, was signed into law on August 25th,1916 by President Woodrow Wilson. Since most of the existing national parks were located in the western part of the country at that time, several new parks were erected in southern states where segregation was legalized. Despite rebuffs from Black American citizens and leaders, in 1937 NPS Director Arno B. Cammerer committed to racially separate facilities in southern national parks, such as the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. He wrote: “There will be some criticism by colored people against segregation. But I think we would be subject to more criticism by the colored people as well as the white people if we put them in with the white people.”

Just as nature investments, namely parks, trees and parkways, were diverted away from redlined neighborhoods, efforts to maintain the status quo or restore White equilibrium were put in place by upholding White wilderness in the governance of national parks. “Wilderness,” a concept created by and for White men, bisects humans from nature and omits the histories of Indigenous people who lived symbiotically with the land before colonization. Moreover, early environmental advocates and preservationists, including John Muir, perpetuated a whitewashed wilderness dogma steeped in anti-Black racism with assertions, such as “one energetic White man, working with a will, would easily pick as much cotton as half a dozen Sambos and Sallies.” The concept of wilderness is rooted in White supremacy and anti-Black racism. That foundation shaped nature legislation that has led to inequitable development of Black and White green space.

In the US, access to nature is determined by race, class, and place. When compared to White Americans, Black Americans and other communities of color are nearly three times more likely to live in nature-deprived areas or in neighborhoods with no access to parks, significantly less tree canopy, and absence of any green or blue space. This nature deprivation often limits Black people from receiving the physical and mental health benefits of Mother Earth. While humans share an innate connection to nature, many scholars have purported that the human-nature relationship is affected “by the justice or injustice of their social surroundings.” Despite these injustices, Black people continue to connect with this majestic Earth for liberty, beauty, and healing.

—

Dr. Jennifer D. Roberts is the Founder and Director of the Public Health Outcomes and Effects of the Built Environment (PHOEBE) Laboratory as well as the Co-Founder and Co-Director of NatureRx@UMD, an initiative that emphasizes the natural environmental benefits interspersed throughout and around the UMD campus. Her scholarship focuses on the impact of built, social, and natural environments, including the institutional and structural inequities of these environments, on the public health outcomes of marginalized communities.

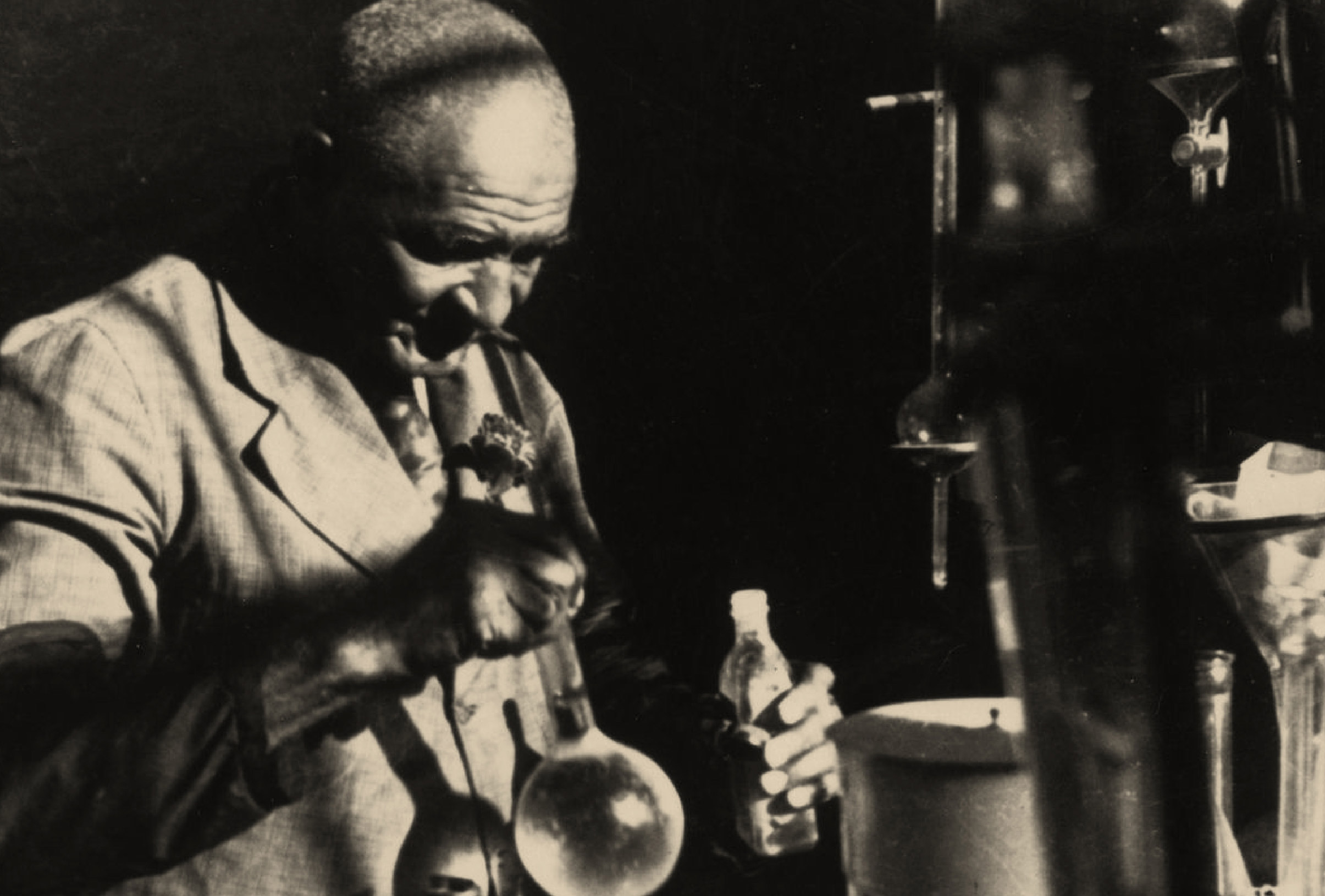

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)