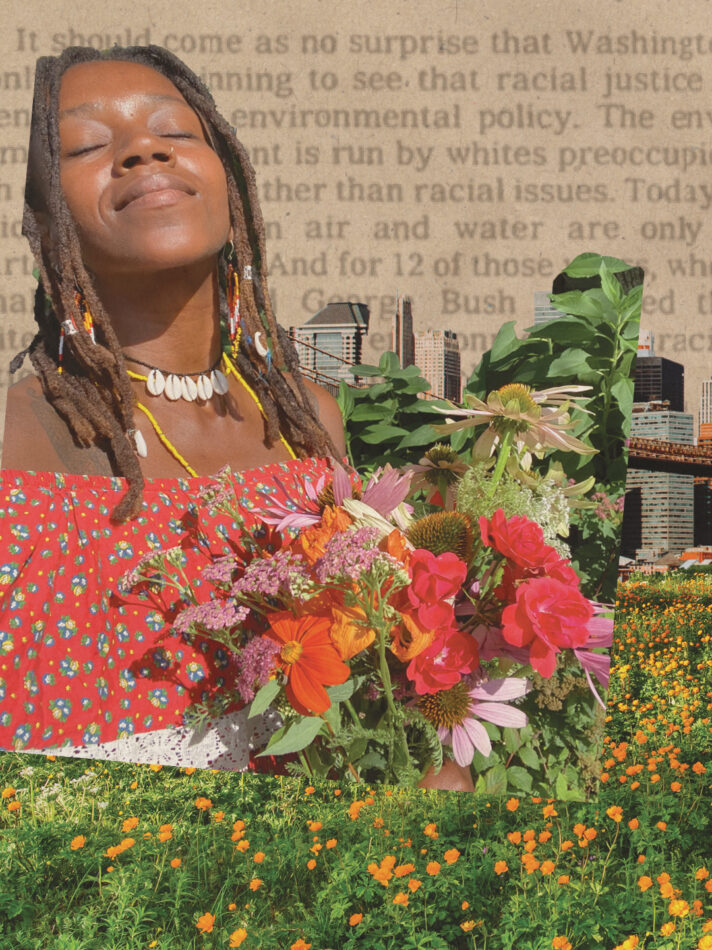

Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

When you think of peanuts, what comes to mind? Perhaps Planters’ Mr. PeanutⓇ character with his monocle, top hat, and twirling cane? Or maybe creamy peanut butter, trail mix, PB&J sandwiches, and sweet chocolate-covered treats? The peanut might just be one of the most common “nuts” grown today, with influences on culinary practices around the world. Although the peanut didn’t originate in the United States, it has an important cultural impact and is here to stay. Beyond its popularity, this plant brings with it some underappreciated, land-healing talents and a unique history.

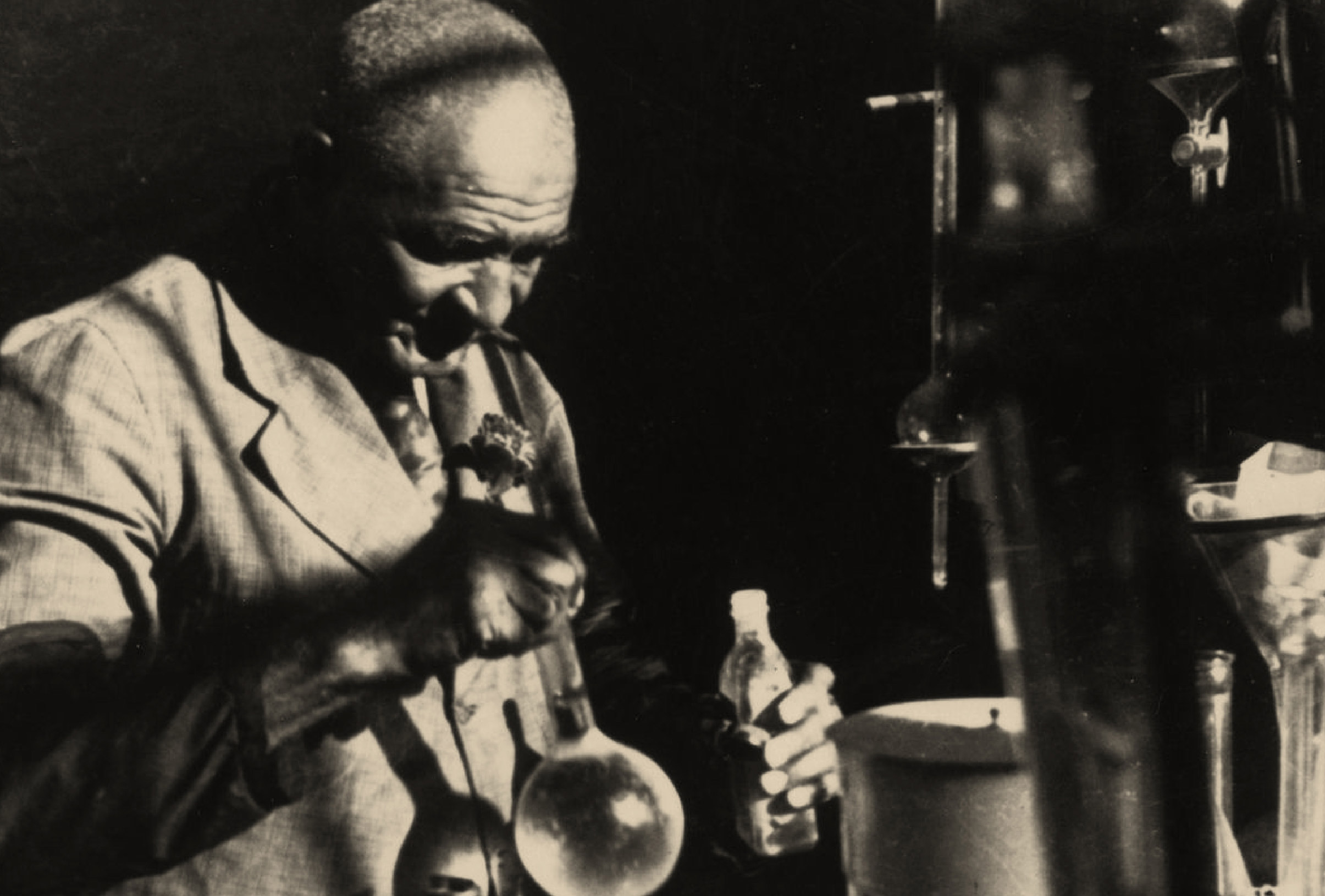

The peanut has a distinct connection to Black prosperity in this country. It was not only made famous for its taste, but also for its unique ecological properties and agricultural impact. George Washington Carver, famously celebrated as “The Peanut Man,” is widely associated with this plant; however, he is less known for his scientific contributions to the Black community during the postbellum age of US sharecropping.

THE SCIENCE OF PEANUTS AND SOIL

You may have noticed the quotation marks around the word “nut.” Well, that’s because peanuts are not a “nut” at all! They are a member of the legume family with peas, beans, and lentils. Like many legumes, peanuts perform fascinating feats of science right beneath our feet. The ecological marvels of the peanut plant didn’t become public knowledge until millennia after its first use and centuries after the peanut’s first appearance in the American South. Peanuts and other legumes are nitrogen-fixing plants that provide nutrient-rich meals for us and supply plant-enhancing nitrogen to the soil.

Nitrogen makes up the vast majority (78 percent) of our atmosphere. It’s the reason the sky is blue and the plants can’t photosynthesize, but atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is not digestible for the plants and animals that depend on it. All this nitrogen fills our air, and we can’t even absorb it—at least not until nitrogen-fixation occurs.

On rare occasions, this process is facilitated by lightning storms—the intense heat of lightning strikes converting unusable N2 into usable nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Most of the time, this conversion is done by nitrogen-fixing bacteria like the rhizobia, located in the roots of legumes, which break down N2 molecules to form NH3 (or ammonia). That ammonia is then ready to be processed by plants as fertilizer, a major component in their production of chlorophyll (the molecule that gives plants their green color and allows them to make their own food).

The artificial fertilizers we use for our gardens and farmlands attempt to mimic this process, taking nitrogen directly from the air and combining it with methane, chemicals, and other inorganic inputs to produce ammonia. However, unlike Earth-healing legumes, man-made fertilizers often deplete nutrients in soils and lead to dead zones in waterways. This is because the excess nitrogen causes soil microorganisms and algae in water ecosystems to grow much faster than they naturally would, using up all nutrients in the area as well as sucking up all the oxygen that other animals depend on.

One of the most famous examples of a nitrogen-caused dead zone in the US is in the Gulf of Mexico where excess nutrients from lawns and farmlands along the Mississippi river have runoff into the ocean—reducing oxygen so much that no life can survive below the surface. The cycle of nitrogen fixation is what keeps life going on Earth. This long-standing symbiotic relationship between peanut plants and their nitrogen-fixing bacteria is the reason why the grass, shrub, and trees around us have enough nutrients to survive . . . and why we too are alive today.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PEANUT

Peanuts are thought to have originated in Peru and Brazil. In the Incan cultures, peanuts served as a tribute to the dead. The Incans placed peanuts in jars alongside the graves of loved ones who passed away. The peanut plant eventually landed in Mexico where it was introduced to Spanish colonizers and transported to Spain as a delicacy of the “new world.” Peanuts became a staple on Spanish ships, a simple foodstuff that made its way to Africa and Asia via Spanish trading and colonial vessels. This is also how the peanut made its way into West African cuisine in the form of greens served with peanut sauce, peanut brittle, and fried peanut balls called kulikuli . . . and from there, decades later to the coastal South as a part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

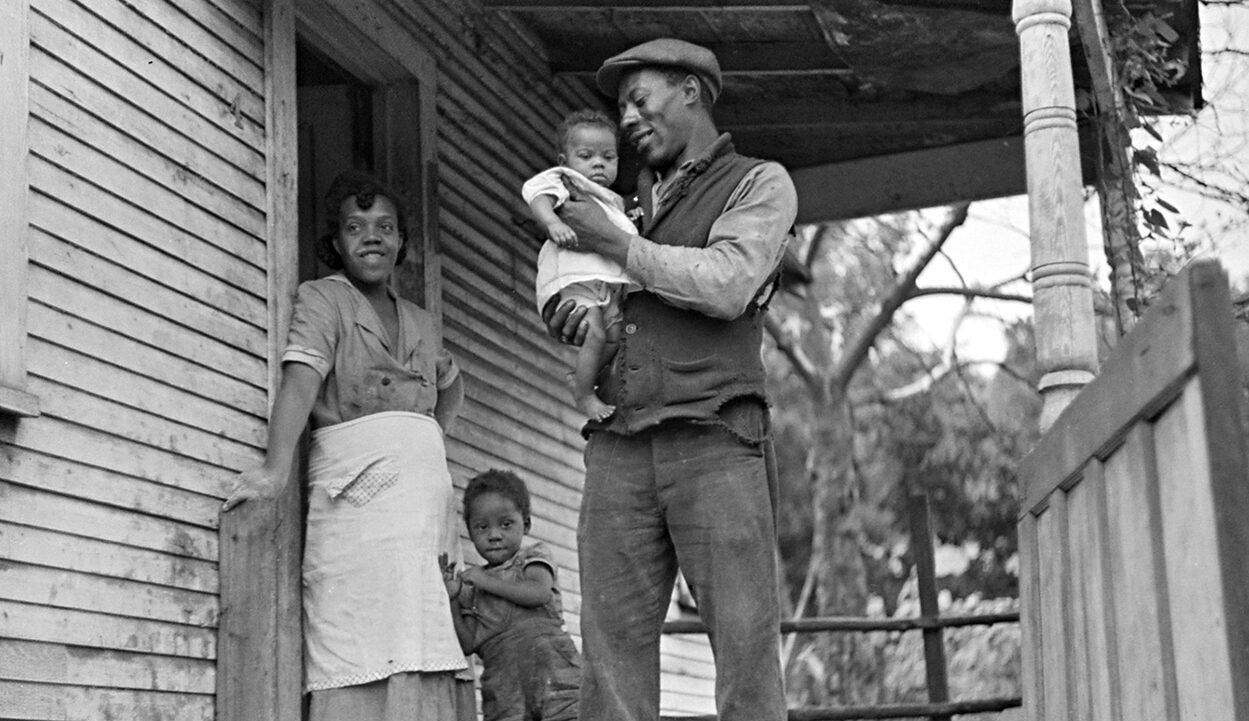

Sometimes referred to as “goobers” (derived from the Congolese word Nguba), groundnuts, or ground peas by early enslaved Africans, peanuts became a poor man’s food in the Southern United States. Before the peanuts’ commercialization, enslaved Africans grew peanuts for themselves. Some think that because of the peanut’s similarity to a traditional West African nut called the Bambara groundnut, the peanut became a critical substitute in traditional stews. The plant soon took up small plots of plantation land as food for hogs before becoming commercially popular in the early 17th century in South Carolina as a substitute for cocoa and as a source of cooking oil. In 1860 during the Civil War, the peanut grew to prominence as food for soldiers in the North and South during bouts of food scarcity.

Four years later, sometime between January and June of 1864, “The Peanut Man” himself, George Washington Carver, was born.

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER

George Washington Carver was born in Missouri in 1864—he was an enslaved child born in the middle of the Civil War. He spent his formative years in the care of White farmers, Moses and Susan Carver, who purchased George’s mother when she was young. When George was a baby, slave raiders kidnapped him, his mother, and his sister and took them to Kentucky for auction; the Carvers were only able to retrieve George. After the Emancipation Proclamation granted (some) enslaved people their freedom, the couple raised George and his brother James as their own and taught them how to read and write. Education instilled in George a fascination with gardening and herbal medicine. As a child, he was known as the “plant doctor” by many of the other farmers in their small community because of his ability to diagnose problems with people’s gardens and fields.

At age eleven, Carver, who was ever passionate about his education, moved to Neosho, Missouri to attend an all-Black school. There, he stayed with Mariah Watkins and her husband. Mariah was a Black woman, nurse, and midwife who introduced him to herbal medicine and the importance of faith. At thirteen years old, he moved out to Kansas in search of a better education, and put himself through school—surviving off of the practical skills he learned from his two foster mothers.

In 1894, Carver became the first African American in US history to receive a bachelor of science degree; he went on to receive his masters in agriculture in 1896. Soon after, he received an offer from Booker T. Washington to teach at the Tuskegee Institute where he established the school’s agricultural program and made numerous other peanut-related contributions to the fields of science and agriculture.

CARVER BECOMES THE PEANUT MAN

After emancipation in the early 1860s, many formerly-enslaved Black folks were forced to turn to sharecropping in order to have shelter and an income. The previous agricultural system that only allowed sharecroppers to grow cotton year after year, depleted the soiland left many sharecroppers with land that barely grew enough food for their own families, let alone their White landlords.

Carver went on to discover a method for replenishing nutrients in the soil that was much cheaper than traditional fertilizers of the time: using nitrogen-fixing peanut plants. This technique allowed Black farmers to grow more for less—with the added benefit of extra peanuts for themselves. He popularized crop rotation, which is now a standard practice for peanuts. Crop rotation is a process that shifts which crops are grown on a particular plot of land to give that soil time to rest. Consistently growing plants like potatoes or cotton or tobacco such as potatoes, cotton, or tobacco often exhausts the soil’s nutrients, resulting in low yields and unhealthy soil ecosystems over time. By trading out a cotton plant for a nitrogen-fixing plant like peanuts between seasons, Carver helped many Black farmers replenish their soil and improve the health and wealth of the ecosystem. This practice is especially useful today for common foods like corn, tomatoes, squash, okra, peppers, greens, and cucumbers—which flourish in nitrogen-rich soils and have a tendency to suck all the nitrogen and organic minerals out of the ground.

Tending to the land using practices that work with the inherent magic of nature doesn’t just nourish the soil, but it is an affordable strategy for mitigating climate change. Healthy topsoil is made up of organic materials and microbes that help suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Regenerative methods like crop rotation maintain these soil ecosystems and help turn our farmlands into carbon sinks that combat greenhouse gas emissions by storing them in the soil organic matter. By working with nature to grow our food, and relying on the same nitrogen-fixing processes that keep us alive, we can increase the amount of food we produce, take advantage of healthy topsoil’s ability to absorb carbon, and reduce the need for artificial fertilizers.

Carver’s popularization of crop rotation and natural soil repletion made him one of the most famous leaders of the sustainable agriculture movement. Today, crop rotation and other regenerative techniques like cover-cropping, no-till farming, and composting are tools farmers use to prioritize their local biodiversity and soil health.

Carver truly embodied the sentiment “we been sustainable.” Although he didn’t invent peanut butter, he did discover over 300 other uses for the plant and was a staunch advocate for a multitude of natural methods for farming that simultaneously created opportunities for Black farmers and protected the environment. Ultimately, his passion for the melding of nature, scientific inquiry, and civil rights brought him (and the peanut) national, timeless fame.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)