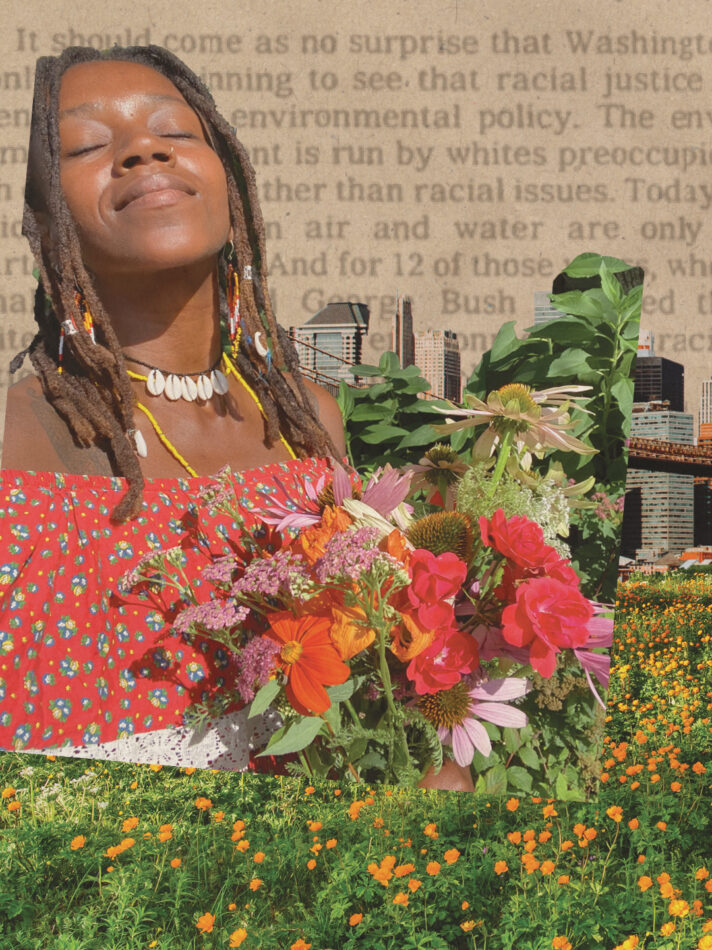

This contributed piece is a part of our Featured Voices series, which invites writers, poets, artists, and creators to explore the various intersections of Blackness and Greenness. “Gardening as a Revolutionary Act” is a personal essay by Deja Curtis that explores family land histories, redlining, and the promise of food sovereignty.

Family Land History

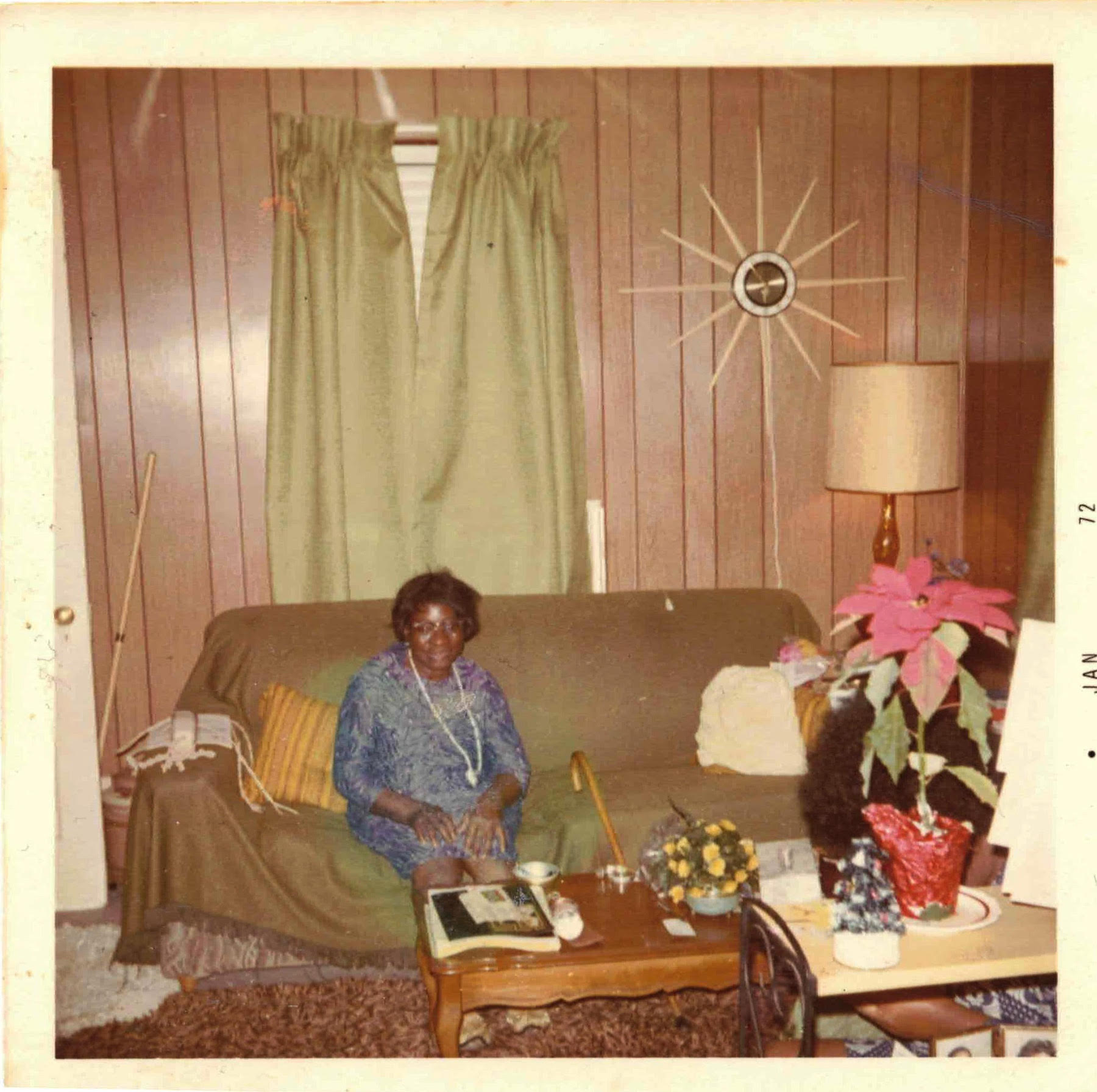

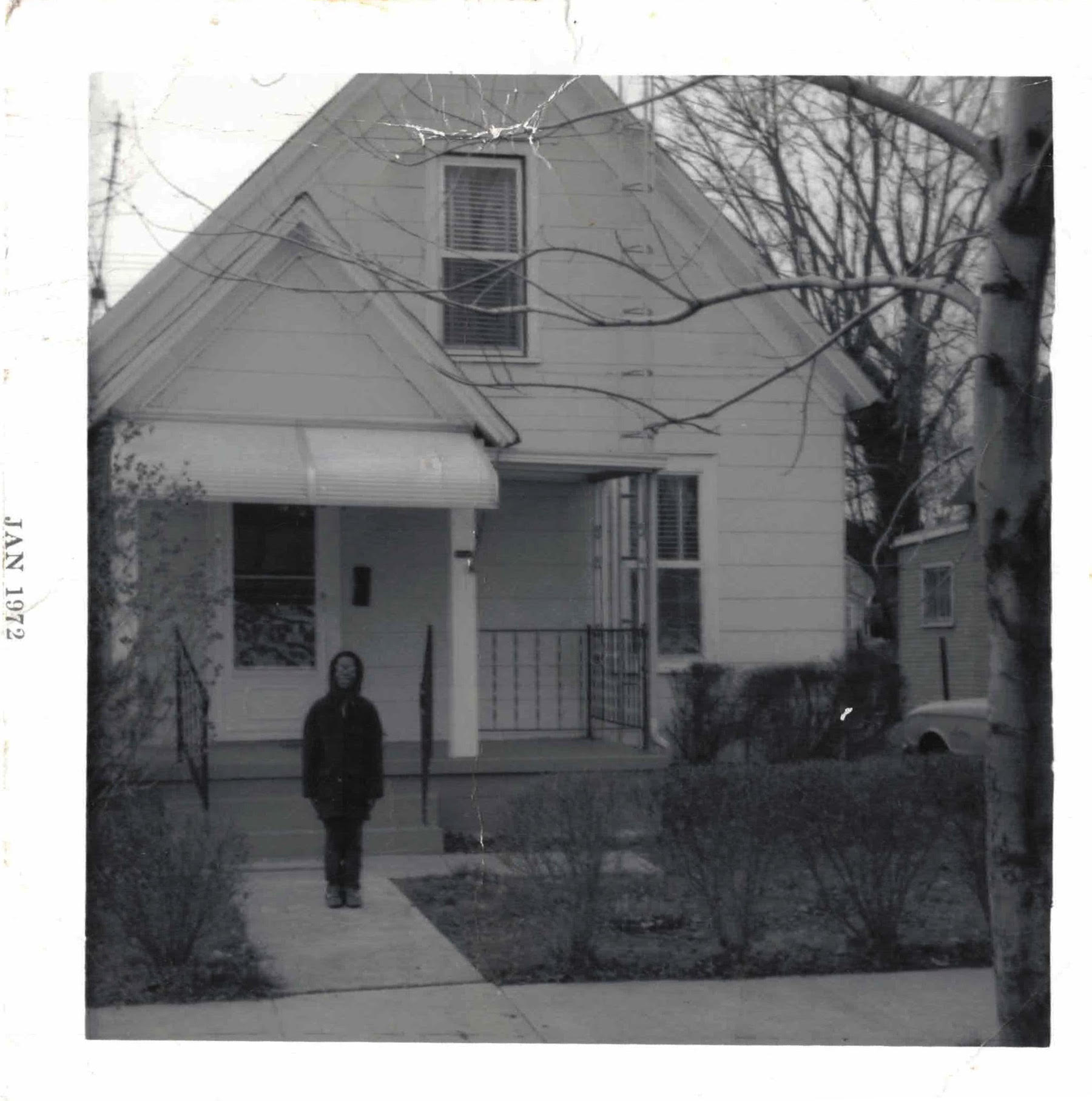

My great-grandmother Dorothy Curtis was born in 1904. She was a disciplinarian, known as cold and distant, even to her grandchildren. She had nine children with my great-grandfather, Roy Curtis, all of whom they sheltered in a four-and-a-half-bedroom house in Springfield, Illinois. The living conditions were so cramped that my grandfather, Ted Curtis, still recounts how grateful he was when his older sister got married—it meant that he would finally get his own room.

Our family’s presence in Springfield extends back into the 1800s. From what we know, portions of our family migrated from the South, likely drawn to the area due to its affiliation with Abraham Lincoln, similar to many formerly enslaved Black folks during Reconstruction. The city may have been the “Land of Lincoln,” but it was only liberal to an extent. Back when my great-grandmother was raising her kids, Black children were only able to swim at the local community pool on Thursdays because the pool was cleaned on Friday mornings.

Given that context, my great-grandmother’s demeanor makes sense. To be a poor Black woman in the United States has never been easy, let alone being a poor Black woman who was responsible for supporting nine children during a time when Black people were only allowed in select spaces. With limited job opportunities and nine dependent mouths to feed, she gardened to help keep food on the table. Within the garden and the home, my great-grandmother was able to call the shots. Every year, the kids reluctantly filed into the backyard, armed with shovels and hoes to prepare the growing beds. The children handled the more labor-intensive tasks like tilling the soil and once the soil was sufficiently prepped, my great-grandmother seeded the beds. They grew onions, carrots, potatoes, and always some type of greens. Those staples were supplemented with meat and eggs from the chickens they raised, creating filling meals for the entire family. My family was not unique in this. Most of their neighbors, along with other Black folks nationwide, also took part in their own subsistence practices to survive in a time where there was a blatant disregard for and denial of their humanity.

FOOD ACCESS FOR WHOM?

A few decades later, my grandfather was growing his own family. Gardening was no longer deemed a necessity due to increased job opportunities,and working two to three jobs covered the weekly grocery store trip. However, food access within Springfield was still far from equal. Major grocery stores had a pattern of opening locations within my father’s southeast neighborhood only to close up shop shortly thereafter— restricting the options to either nearby corner stores or grocery stores only accessible by car.

The term “supermarket redlining” has been used to describe the reluctance, and at times outright refusal of profit-motivated supermarkets to open grocery store locations in cities and low-income areas, often opting for suburban areas instead. Large grocery retailers were (and still are) disinclined to move into low-income areas due to lower anticipated profits, fear of the potential for crime, discriminatory beliefs, and logistical challenges that come with securing property in densely populated regions. Inadequate and unsafe public infrastructure (components of structurally-enforced, race-based segregation) also contributes to poor community connectivity to necessary resources like supermarkets.

Recent discourse has labeled such areas “food deserts” or “food swamps” based on perspective. A food desert is defined as an area that lacks access to affordable and safe food options, while a food swamp refers to a region with an excess in processed food outlets. However, these terms, created from an outside perspective, only characterize a community, rather than address the overall system that allows these patterns to thrive. The term “food apartheid” highlights the race and income-related discrimination built into policies and practices, resulting in unequal access to this vital resource that we all need to survive. A 2015 study based in Detroit (a city commonly referred to as a food desert) found that neighborhoods with Black populations greater than 40 percent typically had less access to large grocery stores. Similarly, studies demonstrate that predominantly-Black neighborhoods and low-income communities have less access to grocery stores nationwide.

By reframing how we discuss and assess food access, we gain a more vivid view of self-defined Black resilience.

As a result, many community leaders have taken the initiative to fill this resource gap themselves. Farmer, food activist, and community organizer Karen Washington is one powerful example of this movement. Washington’s experience of building a community garden with a neighbor inspired her to help develop gardens on vacant land throughout the Bronx. She has since co-founded Black Urban Growers and Black Farmer Fund—both of which are conduits for community and financial support for the Black farmers movement. She also co-manages Rise & Root Farm.

Food Sovereignty

In 1996, La Via Campesina, an international farming organization, coined the concept of food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” The term, created for exploited rural farmworkers and Indigenous people, also describes a concept cherished by Black American communities dating back to enslavement. It is known that many enslaved Africans cultivated their own gardens on plantations, some sprouted from seeds carried from their homelands, providing sustenance and a form of bodily autonomy despite the confinement and cruelty of chattel slavery. Today, there are community groups practicing food sovereignty on different scales to carry on Black folks’ land connections and support self-sustaining food security.

While food sovereignty’s origins have always been community-oriented, current food justice literature often uses grocery store presence as an indicator for food security. This contributes to an undervaluing of other food sources organized and supported by residents. In that same Detroit study, researchers found that there were more than three times as many neighborhood farms, gardens, farmers markets, and food assistance programs compared to traditional food outlets throughout the city, highlighting community resources obscured by blanket terms and research methods. By reframing how we discuss and assess food access, we gain a more vivid view of self-defined Black resilience.

Within the comfort of our gardens, we are able to create symbiotic relationships with the Earth that honor our ancestral ties and help to nourish our physical forms.

Black land connection and the growing of one’s food is an act of resilience that has stood the test of time. The gardens of my great-grandmother and those that came before her are a testament to this—their harvests feeding our family for generations to come. Food sovereignty allows for self-determination and self-sufficiency, both of which are revolutionary within a system that structurally threatens and harms Black folks’ mere existence. Within the comfort of our gardens, we are able to create symbiotic relationships with the Earth that honor our ancestral ties and help to nourish our physical forms. These relationships are integral to Black environmental history and present-day—containing lessons of how to persist in perpetuity.

—

Deja Curtis is a writer, researcher, community organizer, and lover of the outdoors. Her writing leverages her environmental engineering and science background to explore connections between people and the (built and natural) environment. She is especially interested in Black environmental history and its documentation. When she’s not writing, you can catch her laying out in the sun (preferably by water) with her latest bookstore find. She is from Tampa, Florida and currently resides in Washington, DC.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)