Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

When spring blooms into summer and the heat of the season pushes people to trade their layers for swimsuits and sunscreen, American beaches become a popular spot to cool down and have some fun in the sun. These coastal ecosystems have been used for summer recreation for generations and are a sandy home for a multitude of important coastal creatures. Beaches are also connected to the lesser-told history of segregation and Black conservation practices associated with several beaches in the United States, revealing the role that Black people have had in the environmental movement and the inherent connection between Black folks and natural and recreational spaces.

coastal ecosystems

Beaches worldwide are an ecological buffer zone between the high winds and powerful waves of the ocean and populations inland. They’re created when waves deposit gravel and sand along continental edges and wear away at coastal bedrocks, forming a gradual sandy slope where the land meets the sea.

The high winds, variations in sunlight, shifting sand, and inconsistent wave patterns on beaches make them difficult habitats for coastal creatures. To combat these challenges, a number of different ecosystem types have adapted to life on the coast. In the US, the most common of these are oyster reefs, kelp forests, salt marshes, and rocky habitats characterized by bottom dwellers like sea stars, sea snails, and crabs, as well as sedentary, anchoring organisms like barnacles and oysters.

Sandy beaches—those most often used for recreation—help protect shoreline communities from extreme weather events, break down organic materials and potential ocean pollutants, and provide nursery habitats for fish and nesting sites for species such as endangered sea turtles and shorebirds. The shallow, sun-filled waters of coastal ecosystems provide habitat for seaweeds and algae populations, the base level for life in these parts of the ocean. Additionally, as Arctic ice caps melt and contribute to rising sea-levels worldwide, sandy beaches act as an important buffer zone between flood and rising waters near inland communities.

black beaches in america

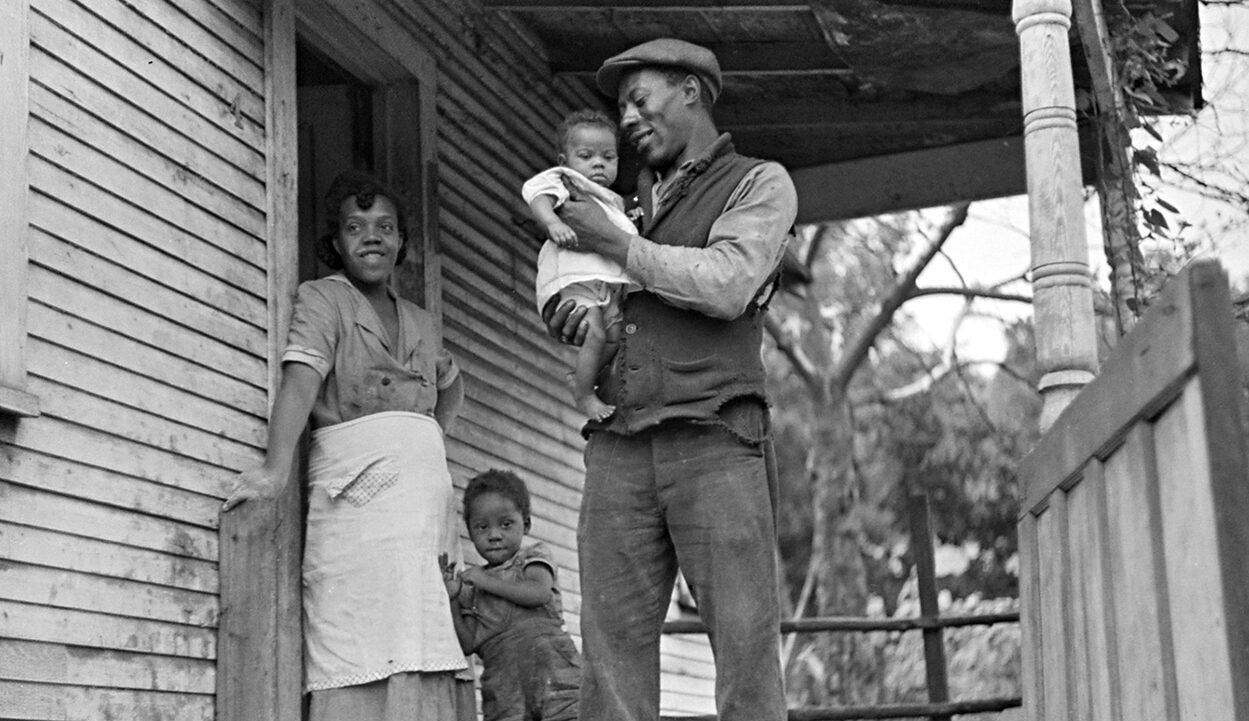

Beaches have also been a critical economic resource for coastline communities in the US, serving as home for fishing and crabbing communities, resort towns, and summer beach weeks. The oldest Black beach resort was Highland Beach which was located in Maryland and founded in 1893. The resort was established by Charles Douglass, son of famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass after Charles and his wife were denied entry into a coastline restaurant in the Chesapeake Bay. In 1922, Charles’ son pushed to turn Highland Beach into the first African American incorporated municipality in Maryland’s history. Eventually, notable advocates and artists like W.E.B. Dubois and Langston Hughes spent time vacationing there in the summer.

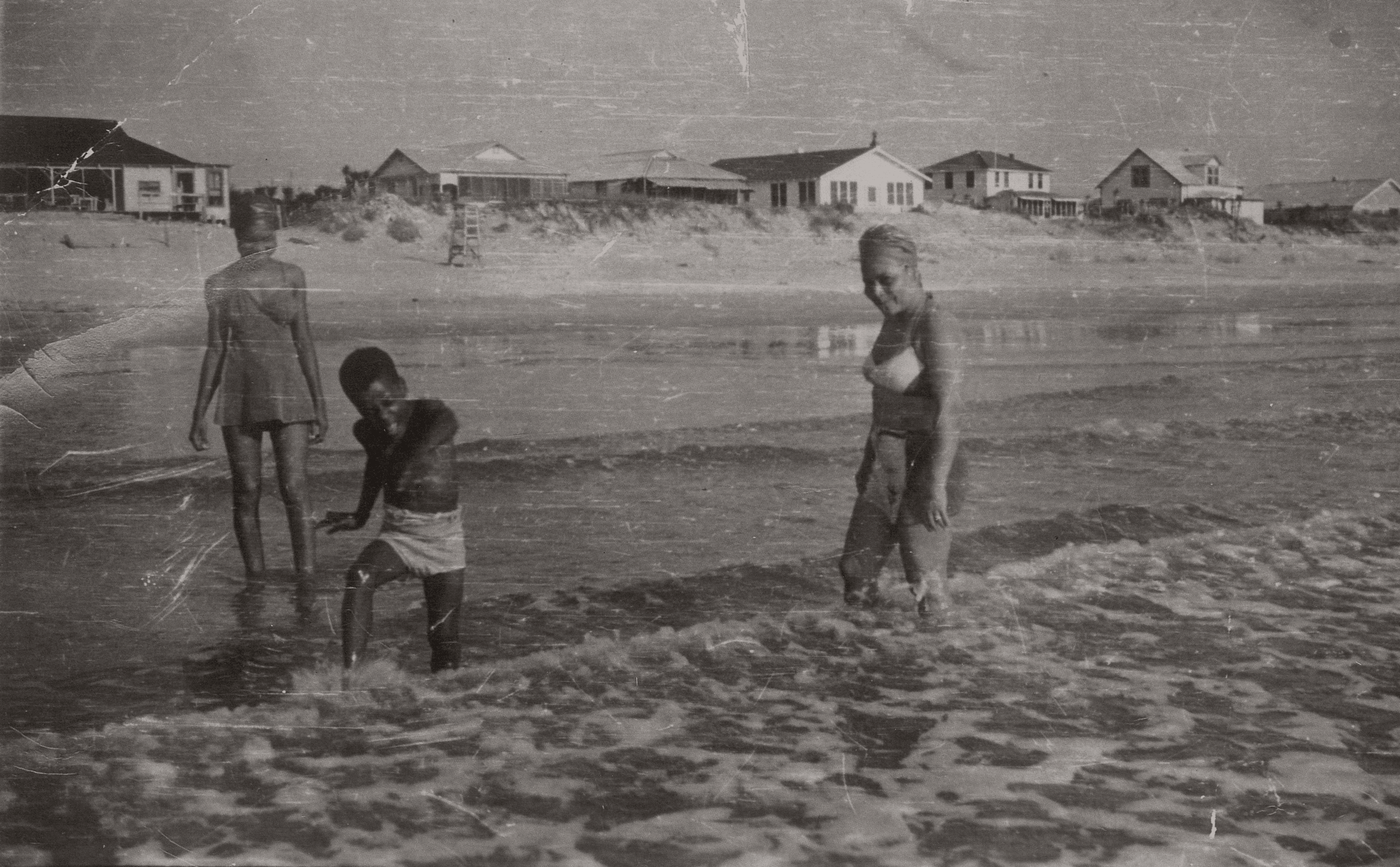

Black beaches like Oak Bluffs Beach at Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, Sag Harbor in New York, and the Gullah-Geechee Islands in South Carolina have and continue to sit as spaces for Black prosperity, investment, excellence, and cultural preservation along the US coast. Despite those facts, beaches have historically been sites of racial division. The 1919 Chicago Race Riot was initiated after a group of White men stoned a Black teenager to death after he accidentally drifted across the color line on the artificial beaches of Lake Michigan. From that point forward, segregation of recreational spaces essentially excluded Black folks from enjoying public beaches. In the South, Black beaches that were provided were often polluted or in hazardous locations, and in the North beaches were segregated using high entry fees or resident-only restrictions that more subtly barred entry for people of color. The lack of access to public swimming locations contributed to one of the most common stereotypes today—that Black people can’t swim, with many Black children in the Jim Crow era drowning at beaches that were remote and less attended to.

One of the United States’ most famous Black beaches also has a conservation story. American Beach, Florida’s first African American beach, was founded in 1935 by Abraham Lincoln Lewis and was known as “The Negro Ocean Playground” for its entertainment, food, and hotels. Environmental activist and opera singer MaVynee Oshun Betsch, also known as the “The Beach Lady” is renowned for giving her fortune away to preserve this beach. Betsch was born in Jacksonville, Florida and spent her formative years visiting the beach that her grandfather Abraham Lewis had established. Years later in the 1960s, although she was making a profitable living as an opera singer, Betsch was key in supporting American Beach after Hurricane Dora and the nationwide drawback of segregation caused people to leave which diminished the quality of the beach. Betsch donated all she had to organizations focused on the conservation of Florida’s coastal organisms and moved from her family home to live and sleep on the beach. She was most recognized for her floor-length locks, colorful lipstick, and six-foot shell-covered frame. The most striking aspect in Betsch’s work was her love of seabirds, ocean invertebrates, and the other ecological structures of the Florida beach. She truly embodied the inherent love and connection between Black folk and natural spaces. Because of Betsch’s conservation efforts, American Beach became a member of the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places.

Although Betsch passed away in 2005, her legacy continues on. In 2014, the American Beach Museum was opened to commemorate the history of American Beach and Betsch’s conservation work. Black beaches in America have stood the test of time as critical spaces for Black nature connection and recreation, preserving the history and culture of some of America’s coastline Black communities.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)