Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been sustained by our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

Stretching along the coastline of the eastern US sits a shallow-water reef ecosystem. Much like the colorful coral reef systems of the tropics, this critical, life-giving underwater community plays an important role in regulating water quality and supporting many marine reproductive cycles. We’re talking about the oyster reefs of New England and the Chesapeake Bay, an ecosystem with an undercovered connection to Black economic growth on the East Coast, and one of the country’s most famous restoration success stories.

Known by some as the vacuum cleaners of the ocean, oysters have a knack for cleaning ocean waters while acting as nursery habitat for local fish and crustacean populations. Oysters are key members of the bivalve mollusk family (along with clams, scallops, and mussels), and can be found in brackish water (halfway between saltwater and freshwater). These marine animals are famous for their non-symmetrical shell structures, their fascinating ability to form pearls, and the sharp formations that they create along coasts and in bays around the world. These shellfish reefs were once prominent all over the globe. Now, more than 85 percent of these reefs have disappeared worldwide.

Known by some as the vacuum cleaners of the ocean, oysters have a knack for cleaning ocean waters while acting as nursery habitat for local fish and crustacean populations.

oystering origins

Over 3,200 years ago, many coastal Indigenous American communities, including the vast Powhatan Nation living along the banks of the Chesapeake Bay, harvested oysters as a source of food in a manner that allowed the crucial coastline habitat to thrive. To this day, large piles of oyster shells combined with other organic Earth materials, also known as shell mounds or middens, remain alongside remnants of community fires and homes in the Chesapeake Bay and the San Francisco Bay area. These mounds were multi-foot tall human-made masses that served as burial grounds, sites to hold ceremonies, and hubs for trade and inter-community interaction. Some of the middens in the Chesapeake have been found underwater, a window into what were previously seasonal campsites for Indigenous fishermen; but in the San Francisco Bay, many of these historical sites have been cut down, cemented over, and transformed into amusement parks, factories, and shopping centers. The disrespect shown to these cultural sites is a point of grief for West Coast Indigenous communities, indicative of the historical erasure of culture and sustainable practices done in the name of “progress.”

In the US, Oyster harvesting was in practice across racial groups in the early 1800s until industrial fishing practices spread from New England into the South, which caused overexploitation and habitat degradation. Oysters were considered a food that crossed between socioeconomic lines and a source of lime for limestone buildings, but oyster extraction peaked in the Chesapeake Bay in the early 1880s before significant depletion prompted states in the oyster-rich region to slow down extraction and create oyster restoration programs known as seeding repletion programs.

Around the time of the oyster industry’s peak, plantation slavery came to an end, marking a new moment in maritime history and economic engagement for free Black people. In the same way that many enslaved people worked as ferry drivers or water workers along the waterways of the Chesapeake, many Black oystermen could trace their start back to slavery. In the years preceding emancipation, Black and White men often worked the waters together, allowing many enslaved people to gain skills they would not have been able to gain on plantations. And after the Civil War, many newly-freed Black people continued to look to the water as a source of opportunity, establishing innovative technologies such as the multiple-log canoe that became the symbol of the Chesapeake Bay and the crab grading system that is still used today, which categorizes crab meat by five basic commercial types: claw meat, claw fingers, jumbo lump, special, and backfin.

oystering and black economic prosperity

Although oystering was famous in New England, the Chesapeake Bay became the primary supplier of oysters in the US. The Bay was also a cultural and economic hub for Black Americans who wanted to take advantage of postbellum seafood opportunities in Maryland and Virginia. Just outside of the Bay, Sandy Ground, a famous oystering community emerged —located in modern-day Rossville, Staten Island. Sandy Ground was thought to have been established before the Civil War in 1828 by Captain John Jackson and became a central hub for maritime trade between New Jersey and New York State. Sandy Ground remains one of the oldest surviving communities in the US that was founded by free African Americans. It served as a haven for many Black oystermen who wanted to escape unjust oyster laws that often prevented free Black men from operating their own boats without a White man in the South. Black oystermen who hailed from New York to Maryland settled in the region, and found that the knowledge they gained about oystering while enslaved translated into a profitable set of skills and an opportunity for professional autonomy. Although oystering was still a limiting profession to many newly-freed Black people who endured discrimination and undue economic oppression, the profits were better than those of the available sharecropping roles. Overall, oystering was a profession that allowed Black men to act as their own bosses, providing a new and liberating sense of self and economic independence from White industrial America.

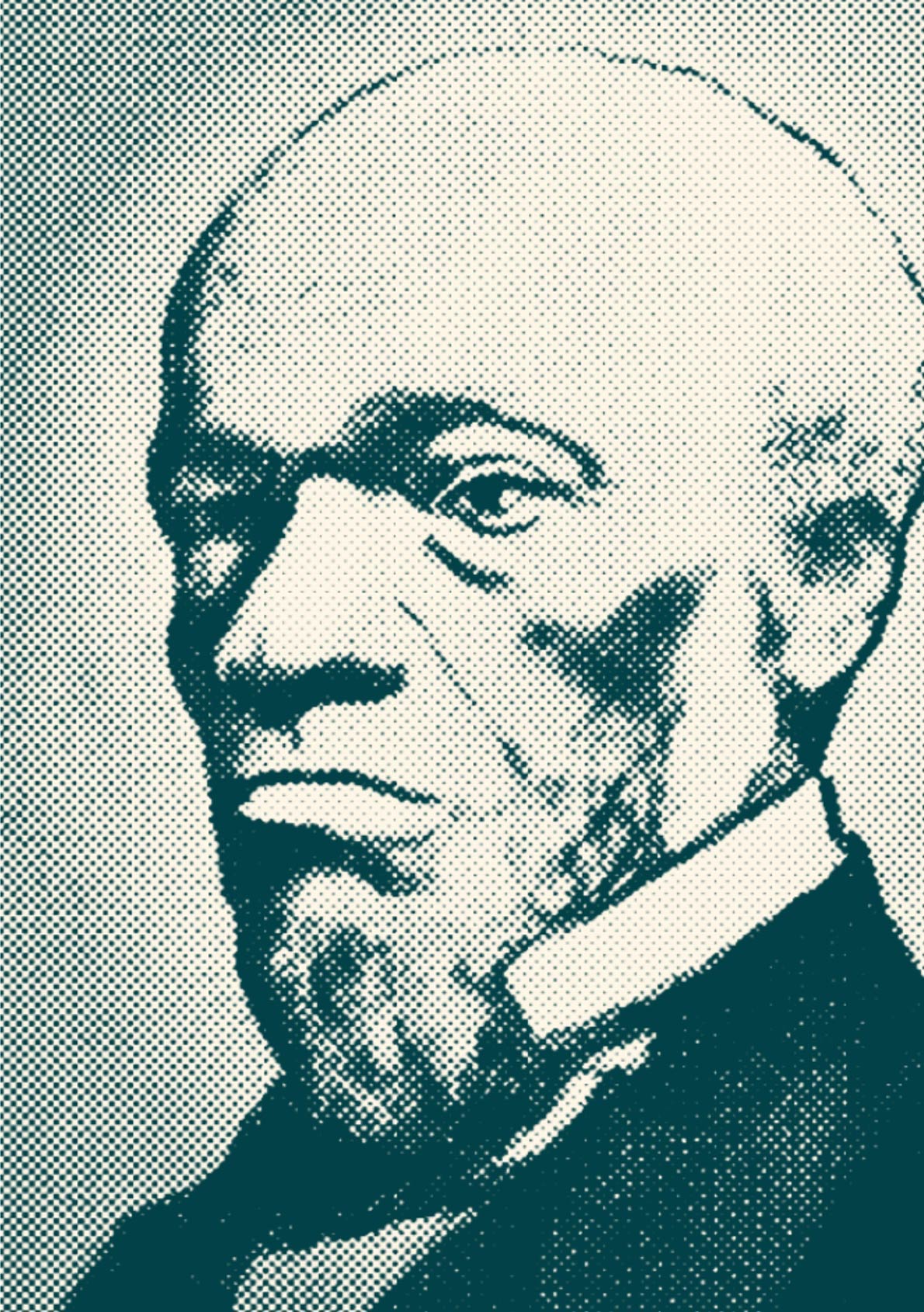

As oyster communities like Sandy Ground became prominent along the coast, oystermen like Thomas Downing made names for themselves as restaurateurs. Downing was born in Virginia in 1791 to formerly-enslaved parents. He spent his days digging for oysters within the waters of the Chesapeake. His childhood in the warm Virginia bay was foundational to his development as a maritime entrepreneur. In the 1820s, during the steady growth of the oyster industry in New York, Downing made his way up to New York City to open what became his famous Oyster House just five years later. Over the years, he catered to celebrities and claimed his own fame from dishes such as oak-roasted oysters and oysters in a half shell.

Downing’s work earned him widespread respect and notoriety. On the day of his funeral in 1866, many New York Chamber of Commerce members attended the service—a day in which the Chamber was famously closed. He remains known as the “Oyster King of New York”—a title he received when the city was considered the oyster capital of the world. In the decades following, Black Americans continued to act as irreplaceable players in America’s global oyster establishment.

oystering today

The early 1900s brought a collapse of the industry with oyster stocks depleting to near extinction due to overharvesting around the world and growing fears of typhoid spreading in the New York Harbor. Many of these famous oyster towns disbanded as community members left for factory jobs. Sandy Ground still holds the largest number of direct descendants of those first oystermen, and the community remains rooted by a shared history and set of longstanding traditions. In 1929, coast state governments replaced oyster harvesting with oyster repletion seed programs aimed at reviving public coastlines and restoring the oyster beds that had been displaced by massive kelp forests. The work took decades and was hindered by unexpected fungal pandemics, predation, and competition for space. Today, even with ongoing efforts in the US and Australia, international oyster populations are devastatingly low. Despite these challenges, oysters and other mussels remain a sustainably-harvested culinary staple within most East Coast communities and across the US; and nonprofits and state governments have made enough restoration progress along the East Coast, primarily in the Chesapeake Bay area, that the region is being touted as a global success story.

To this day, the oystering craft is still practiced by descendants of those oystermen who struck out along the New England and Chesapeake waters in search of economic independence. Villages like Hobson, along the James River peninsulas, and oyster communities around Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes in Louisiana also remain as vestiges of the many historically-Black oyster communities that used to thrive along the US coast. Oystering continues to be a way to uphold decades of recipes and traditions—a tribute to those who took back their freedom one shellfish at a time.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)