Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

The Georgia Peach is a summer delight that symbolizes the sunny, fertile lands of our country’s southeast Peach State. You’ve likely tasted a Georgia peach—it’s velvety texture and almost undeniably sweet flavor has fresh sticky juices that coat your fingers with every bite. Although today, this fruit is a welcome addition to grandma’s cobblers and pies, the Georgia peach, like many structures and symbols in the United States, was founded in institutions of slavery. In fact, the entire peach industry is steeped in the mistreatment of Black and Brown communities. During the antebellum period, the peach served dual roles: a widely disregarded food source by White plantation owners, and a treasured resource to many enslaved Africans who sought freedom in America.

PEACHES THROUGHOUT TIME

A member of the prunus tree family like plums and apricots, the pink, yellow, and orange peach fruit is known for its large, hard seed center pit, and originated in Eastern Asia. Some of the oldest peach pits were unearthed amongst the ruins of neolithic settlements along the Yangtze River Valley in China.

The peach plant’s fast-growing nature and resilient seed made long-distance travel easy. The peach traveled along the Silk Road from China, then made its way into Rome and Persia, and eventually arrived in Western Europe where it was transported across the Atlantic ocean and settled in the old American South. It arrived on the east coast in the mid-sixteenth century, carried on Spanish colonial vessels. By the time settlers established Jamestown, the peach tree was already growing easily and readily across the region, as it was adapted by Indigenous tribes of the South who selectively bred the best peach plants, enhancing the fruit’s “genetic heritage.”

Over the course of the next couple of centuries, the peach became a common and accessible fruit, making it an easy and cheap snack for those enslaved on Southern plantations. It wasn’t nearly the delicacy or the symbol it is today. Peach trees commonly lined fields and Southern walkways, and became easy pickings for local livestock. On occasion, farmers fermented the plant to create syrups and brandys. The plants were considered a “feral resource,” though it wasn’t unusual for plantation owners to create peach festivals surrounding the fruit’s harvest time. The fruit also served as a welcome resource for many who escaped slavery and found themselves hiding in peach orchards throughout the American Southeast.

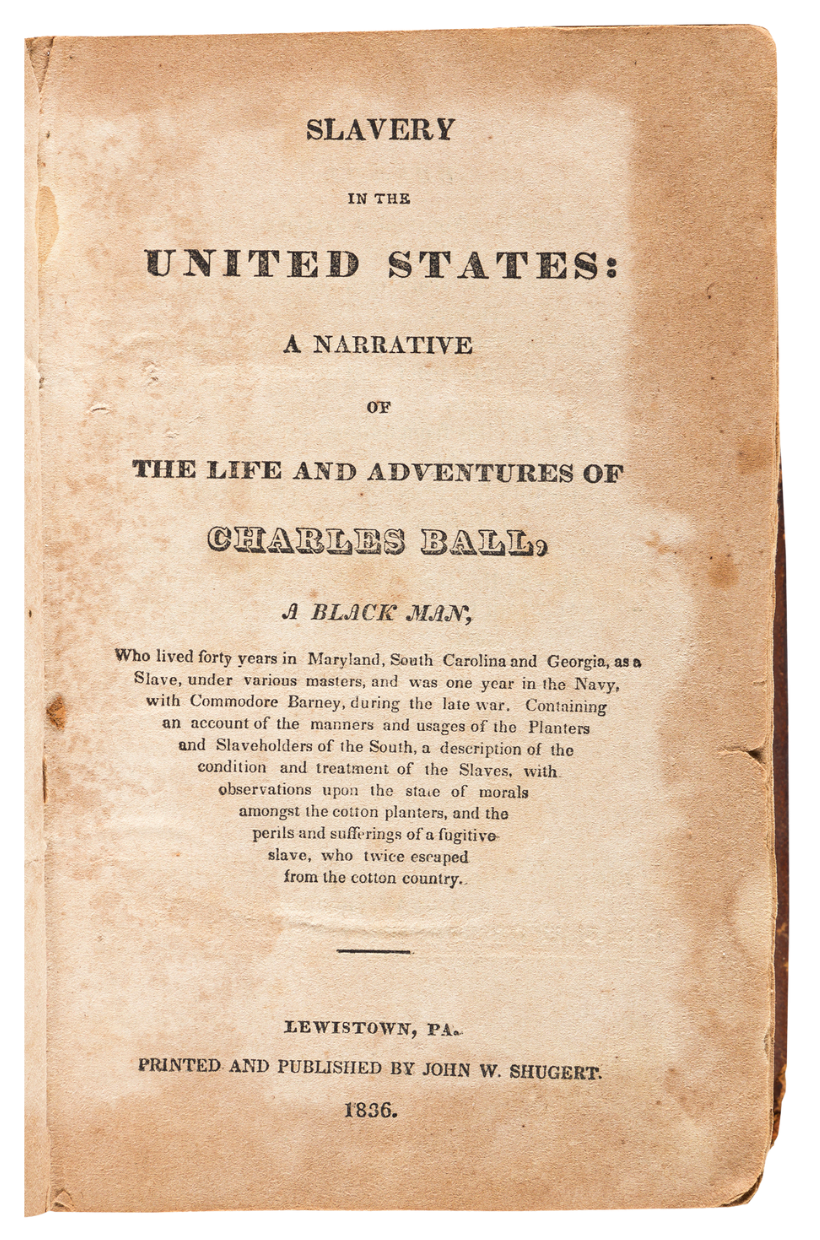

charles ball and the antebellum peach

“When the peaches ripened, they were guarded with more rigor—peach brandy being an article which is nowhere more highly prized than in South Carolina. There were on the plantation, more than a thousand peach trees, growing on poor sandy fields which were no longer worth the expense of cultivation.”

Charles Ball’s narrative is one of the rare documentations of the deep-rooted connection between the peach plant and Black history. For over forty years, Ball was one of the many enslaved people who worked the cotton, apple, fig, and peach orchard fields on plantations in Maryland, South Carolina, and Georgia. In his story, he described early life instances of the peach as a highly prized foodstuff, a key ingredient in the making and selling of peach brandy. He spoke of his first Christmas on a cotton plantation in Maryland, where he was given a drum of peach brandy, some pork, and less than one day’s rest before being sent back to the fields. He shared his journey to freedom, an escape that took him through forest, river, swamp, and a ripe peach orchard field in South Carolina that was “laden with fine ripe fruit.” Ball described quickly filling his pockets and hat with life-saving peaches before moving on. He recounted incidents of kindness received from both Black and White South Carolinians in his travels, a family who gifted him a breakfast of cold meats and a drum of peach brandy before sending him on his way. Many stories of other enslaved people mirrored Charles Ball’s narrative—long, sad, and heartening stories steeped fully in the ubiquity of the Southern peach.

…with emancipation and the ‘death’ of the free labor system that powered the cotton industry, plantation owners in the South were looking for a new, less contentious cash crop.

The peach was a tertiary crop during the antebellum period. Despite the fruit’s significance to many Black people, the South was too preoccupied with the production and sale of cotton and the institution of slavery to create a significant industry out of this fruit. But with emancipation and the “death” of the free labor system that powered the cotton industry, plantation owners in the South were looking for a new, less contentious cash crop. The peach was an easy pick. It was delicious, well-known, abundant, and came without the same bitter taste of injustice that much of the US associated with cotton. Peach tree numbers increased five times between 1889 and 1924. Peach blossom festivals were held from 1922-1926, an attempt to recharacterize the peach belt (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida) in the name of a less harsh, sweeter Southern crop. It was a clean slate.

the modern day peach

Except it wasn’t a clean slate. The system that revitalized the Southern agricultural economy around pit fruits like peaches, was very much dependent on the same systems of overwork and underpaid labor established during slavery. Not to mention the peach’s harvest time was a direct contradiction to cotton; plantation owners still required a full-time staff to mill the cotton in the winter and the peaches the following summer. Unlike picking cotton, the peach industry was not one to be streamlined or mechanized: the fruit’s fragile skin made hand labor a necessity. As a result, the growth of the peach fruit market, particularly in Georgia and like much of this country, was built off the backs of economically-enslaved Black sharecroppers.

By the end of Reconstruction, a plant that was once so accessible to Black people—as a throwaway fruit, sure, but still a source of sustenance and celebration—had become too expensive for the growing number of Black sharecroppers. The peach’s rosy soft complexion became synonymous with the Southern belle—rosy cheeks, fair skin, and a skewed innocence made inaccessible to Black southerners. As the product grew more and more popular, and as slavery transformed into institutionalized systems for segregation, abuse, and discrimination, the divide in the production and the consumption of the fruit also grew.

Today, the Georgia peach remains a symbol of the growth and prosperity of the South. While it makes up only a small portion of Georgia’s economic output, it marks a critical starting point in the state and the region’s transition away from cotton postbellum and into the fruit markets it’s currently known for. As we enjoy our Georgia peaches every summer, let’s be reminded of this fraught history and uplift the ancestors whose very lives and livelihoods built what is considered a symbol of prosperity across the South.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)