The Community Spotlight series highlights Black individuals and entities who are creating healthy, sustainable, and just futures. In this story, we feature Sheryll Durrant, the resident garden manager and community garden steward at Kelly St. Garden. Sheryll talks about her upbringing in Jamaica, and reconnecting with agriculture and activism after migrating to the US. This story has been edited for length and clarity.

A “Rich Existence” Close to the Land

I grew up in Kingston, which was not like Cacoon, Hanover or River Head, St Ann, the rural areas where my parents are from. Even though both sides of my family engaged in a lot of agriculture, I didn’t farm. From what I saw growing up in Jamaica, agriculture was steeped in poverty. Living in an urban environment with parents who came from poverty, I wanted something else for myself. So, my path was to do well in school and migrate overseas for college. When I first arrived in the US in 1989, I lived in the Bronx while I went to school. I got my Bachelor of Business Administration degree and went into corporate America.

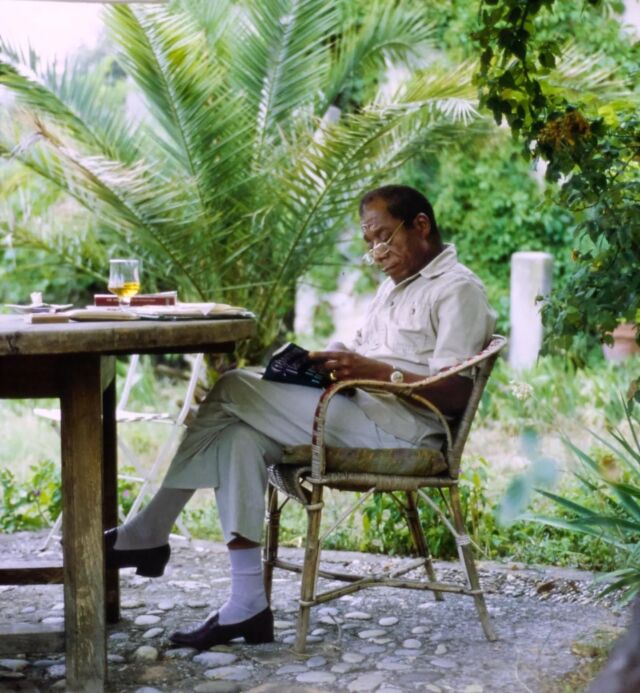

Every time I talk about this story, I realize that I was brought up in a system where a certain type of existence equated to success. Living close to the land and growing your own food was not part of that. Now looking back, there was never a time that I went to the country and we didn’t have a great meal from food harvested by my great-grandmother, grandaunts, or uncles. I see that it was a rich existence because they always had food. Now that I am in this work, I have had a reawakening and appreciate how they lived close to the land.

Every time I talk about this story, I realize that I was brought up in a system where a certain type of existence equated to success. Living close to the land and growing your own food was not part of that.

Today, my work is steeped in community gardening and urban agriculture, and I garden and farm all over New York City. I’m the resident garden manager and the community garden steward at Kelly St. Garden, which is on Kelly St. in the South Bronx near Hunts Point.

I earn a living with my day job as the Food and Agriculture Coordinator for the New York New Roots program at the International Rescue Committee (IRC). I help refugees and asylees reconnect with land. In my work alone, I get involved with community engagement and activism to foster my work and learn about my own journey.

A Reunion with the Land

In my early 30s, I reconnected with food in the way I connected with food in Jamaica. I started volunteering at Sustainable Flatbush. I connected to a lot of Caribbean people and remembered my foodways and the ways my parents gardened. I grew food that was both culturally relevant to me and foods that I had become accustomed to eating in America. It led me back full circle into something that I had abandoned because I thought it wasn’t relevant. Working with the land wasn’t something I considered part of me or my career. My work began to grow as a result of that, and I began to realize how growing food is connected to justice. The other day, a bunch of us were sitting in Kelly Street Garden, discussing how much garbage was in the South Bronx. When we go to Manhattan, the streets are clean. These things are all connected to what justice is and how people are treated in their communities. This is connected to us demanding our place as Black and Brown people in a society that has historically marginalized us. It is part of healing and addressing the trauma and the oppression that infects our communities. It took me being involved in community spaces to actually be able to connect with this and journey through this.

The planet has taught me to look at justice in a different way because land is so important to our freedom and liberation. When I work with the IRC refugees and asylees—one of the first things they ask for throughout the different surveys is, “Where can I grow my own food? Where can I connect with land?”

The planet has taught me to look at justice in a different way because land is so important to our freedom and liberation.

Meeting Kelly Street Garden

I was introduced to Kelly Street Garden while doing community work around data collection. They were looking for a resident garden manager, so I applied for the position. Even though it’s not currently a paid position, it’s about living in the community, working in the community, and stewarding this garden with the community.

Community gardens sprung up in the neighborhood in response to “the decade of fire” in the Bronx, a massive disenfranchisement of a Black and Brown community in the 1970s. I hear stories from residents who have lived here for decades around the time when there was no electricity, running water, or heat—but they reclaimed their communities through sweat equity.

Through this era, buildings were renovated on my block and the community gardeners wanted this space to become a community garden. Once the gates to Kelly Street are open, I don’t care where you come from. That’s what I love about the space. It is about the land. It is not about me, it’s about what the land is asking us to do. Once you acknowledge that and you accept it, you will find a place at Kelly Street Garden.

Before I go home to my apartment, I walk the length of the garden and sit in the space. I have to see the garden every single day, even when I’m not working, because it lifts my spirit.

Connecting with the Land in Urban Spaces

I think we are disconnected from our environment. We’ve become so accustomed to the grind and the commodification of everything that we can’t just be. One of the things I love to do when I’m in Jamaica is walk barefoot on the soil. But how are you supposed to do that when everything is concrete and steel? Simple things like putting your hands in the soil are important. When microbes in the soil touch your hands, it has a transformative effect on your being. When I come to a place like Kelly Street Garden or even a community farm, it’s like a green oasis. Even though there is a cacophony of cars and planes, I can still find peace in this area. Once you see how integral every aspect of nature is, you have a much more humane approach. This is biology, so there’s a reason to put your hands in the soil. Land is essential to our spiritual and physical well-being.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)