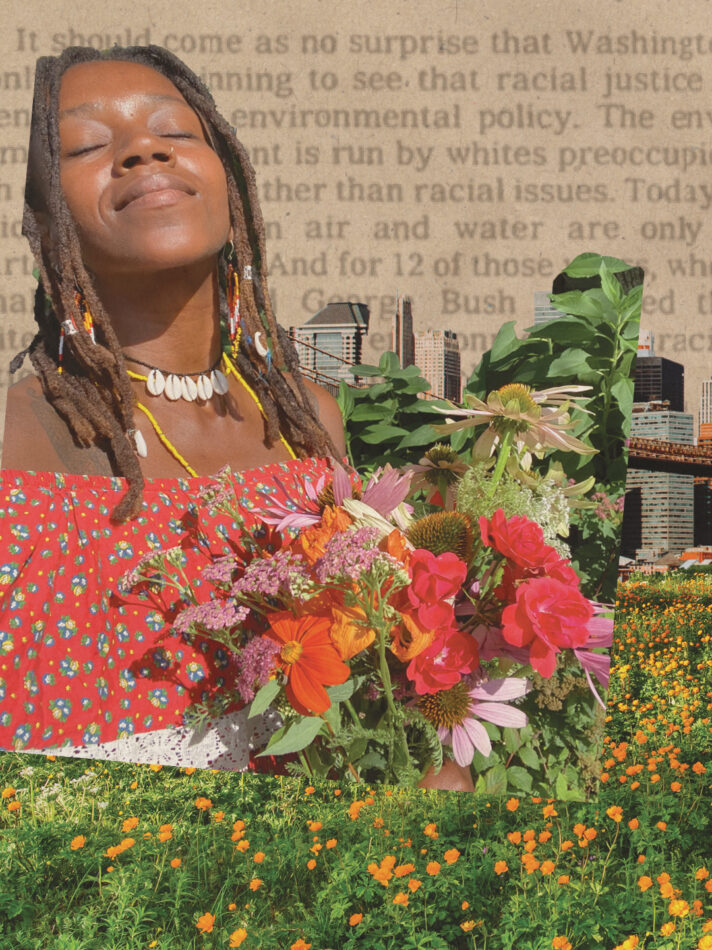

The UNEARTHED series documents Black land histories, celebrates ancestral knowledge, and uplifts our personal connections to place through in-depth interviews. Land histories encompass memories, family stories, inherited recipes, and personal connections that shape the character and legacy of a specific place. Each story is a joyful call to action to share our stories, celebrate our heritage, and renew our kinship with the natural world.

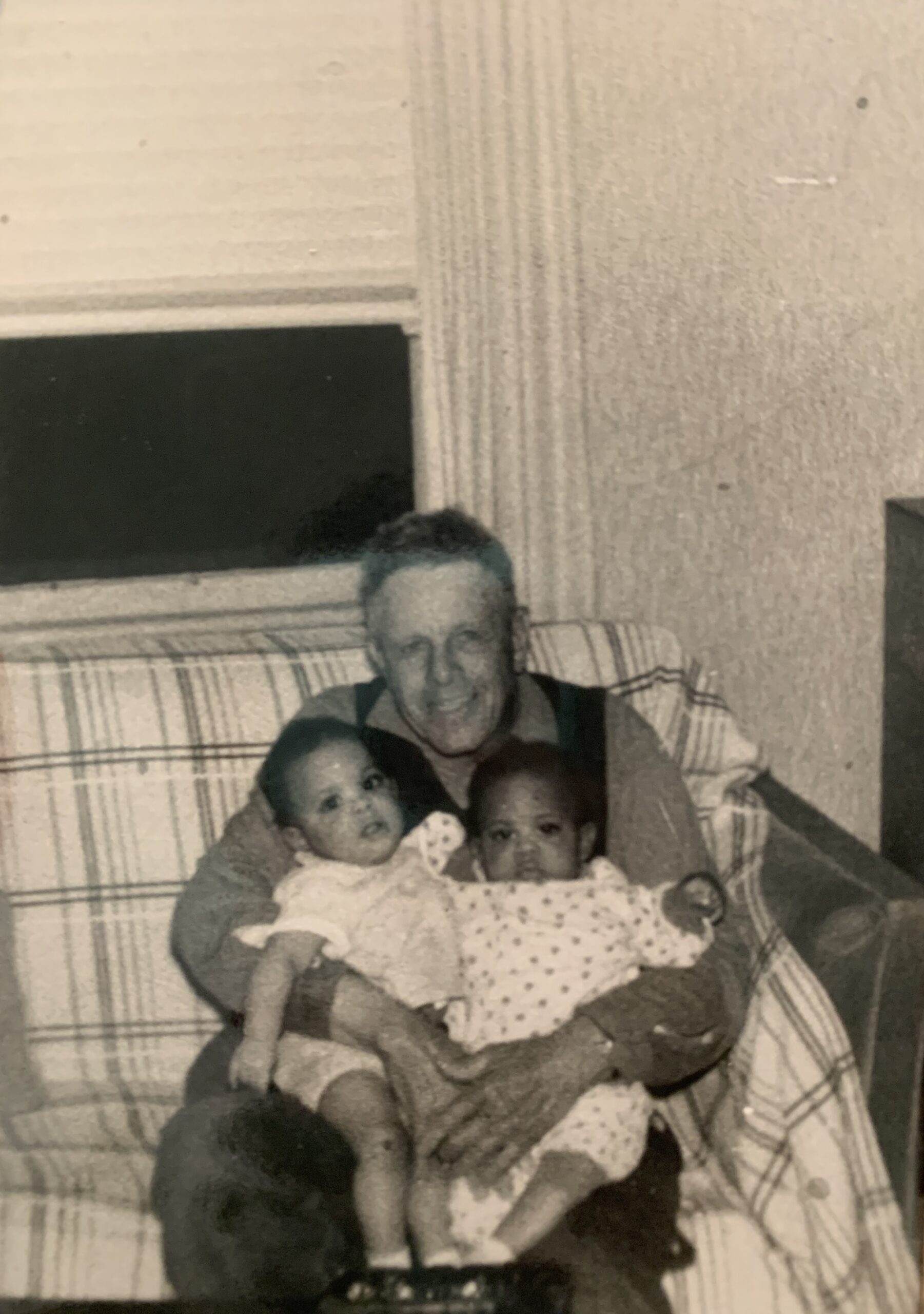

We are lucky to have been raised alongside land we call home. For almost one hundred years, my family has tended to a large, lively farm plot in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. This property was purchased by my great-great grandfather, Carter Jones, in 1925 and has since been passed down through the daughters—from my great-grandmother, Hazel Furr, to my grandmother, Elaine Tutman (Nana Banana), and to my mother, Lisa Tutman-Oglesby. I am a member of the next generation in line to steward this land. As I grew up, I visited the family farm often, watching my Nana in the gardens or joining my late Poppy (my grandfather, William) on walks. This space has been our foundation.

I spent the summer of 2022 living on Five-Star Farms. Between trips to DC for my internship, I gardened for the first time on our land. It was a welcome reprieve to exist in such untarnished outdoors. I cherished the moments spent playing with my uncle’s eager lab River Molly, walking the grounds, and visiting the larger adjacent family property, Jones Farm—still managed by my now ninety-six-year-old great great-aunt Argie. I enjoyed watching the fireflies flitter like will-o-wisps under twilight and witnessing the wild berries mature from flowers to fruit. What I most appreciated was sitting in conversation with my Nana and Uncle Fred, and learning about our family’s connection to the land and landholding knowledge.

In mid-August, I spoke with my uncle, Patuxent Riverkeeper Frederick Tutman, and my Nana, Elaine Tutman, respectively, to discuss our family farm’s history. From these rich conversations, I learned more about my family’s history, what it takes to run a farm, and how I might be able to continue this important legacy and our longstanding affinity for the natural world.

Cameron Oglesby What do you call home?

Elaine TutmanMaryland. Upper Marlboro and this house on Queen Anne Road. It’s home to me because of the familiarity with the seasons, with everything. Like right now, the sun comes up, right about there [points out the dining room window toward the narrow road in front of her house], facing the east. In the winter, I know exactly where the sun’s going to rise. Right there [points behind her through her bookshelves in the direction of the massive adjacent field]. I know where it’s going to be. I’m used to summer, spring, and fall here. And knowing where the sun’s going to come up and go down. It’s familiar to me. I was a little discombobulated for all those years we lived away from here because here I’m comfortable. I have always felt like I belong here. I know where things are. It’s kind of like my place.

I wasn’t aware of the importance of that until we lived in two places. We built this house in Maryland in 1962 and decided to take an assignment for the Peace Corps in 1965. We lived in West Africa, just above the equator. So you have a different set of seasons. We also lived in Tanzania, just below the equator. There the sun came up at seven and went down at seven. However, we always knew we were coming back to Maryland because this is home.

I wrote something on this, for a photo book called Belonging published by Taking Nature Black and the Audubon Natural Society. In the book I say, “I have spent most of my eighty-six years in or about the location of the photo shoot. As a child, these were the woods that I played in, where I carved names on a birch tree the day President Franklin Roosevelt died. The tree is still there. I dug black clay from the creek bed for making pottery bowls and had the thrill of finding Indian arrowheads thousands of years old. I hunted squirrels with my grandfather, helped to plant tobacco, fed chickens, and milked cows. When I walk this land, breathing clean air and soaking up bird song and country sounds, it inspires me to be a good steward of the farm that has been in my family since 1925.”

“When I walk this land, breathing clean air and soaking up bird song and country sounds, it inspires me to be a good steward of the farm that has been in my family since 1925.” Elaine Tutman

Frederick TutmanThis farm is my home. When I was a kid in the 60s, I didn’t really know or it didn’t occur to me that other people didn’t live this way too. At that time there weren’t many houses on this road, the road was much narrower, and it was very much a rural farming community. There weren’t many phone lines that came down here. Most of the adults I knew were people of color. There were White people in the neighborhood, but I didn’t have any reason to know them.

I didn’t really understand until I was an adult that I am kind of a nature guy. I feel much more at home around woods and water and places that are unbuilt. Living out here has been a great opportunity to build a home on land that not only my family had owned for a long time, but that I also have a personal connection to. As a boy, I knew every inch of this place from hunting, walking, fishing, exploring, building tree houses, and doing farm work. We’ve been very lucky.

CO What’s the story of how the land came into our family? I have read that the legend is that the property was left infertile and untouched after the land was cursed by an innocent man who was hanged from one of the farm trees. What circumstances brought great great-grandfather Carter to the property?

ETMy grandfather’s father (my great-grandfather) had a lot of land. And my grandfather Carter and grandmother Eva were tenant farmers, working for other people. But grandfather Carter wanted his own land. So that’s why they bought this property.

As I heard the story, my great-grandfather didn’t give my grandfather Carter land. He gave my great-uncle Jack land. He gave land to my great-aunts. But for some reason, he did not give land to my grandfather. It’s said that he thought my grandfather was not a serious person, and that he would fritter away any property given to him.

But it was my great-uncle Jack who gave away the land he received, frittered it away in my lifetime. And one of my great-aunts died young, and her land went to her husband. So the land was no longer in the family. My grandfather Carter was one of the only ones not to fritter his own land away.

That’s probably why my grandfather Carter made his will the way he did; he left the land, not to his daughters, but to his grandchildren—my generation—to keep it in the family. He felt that if he gave land to his daughters—he had five daughters—their husbands would talk them into selling it because they wanted that quick money. He wrote in his will that his daughters have use of the property as long as they’re alive and when they’re all gone, whichever of the grandchildren are left gets the farm. Now there are only three of us left.

My grandfather Carter bought the land in 1925. He and my grandmother Eva became landowners and held onto the land. We started out with 188 acres, but when the Great Depression came in my grandfather sold forty of those acres so that they could keep up with their mortgage payments until the farm was all paid off. They stuck it out and they worked hard. When the war was over, White people could get loans to buy tractors or equipment or upgrade everything, whereas Black people generally did without that support.

Now we—me and my children Fred, Paula, and Lisa—own about twenty-six acres (Five Star Farms) and the other 122 remain in the care of my Aunt Argie, the last remaining daughter of granddaddy Carter (Jones Farm).

coWhat were some of your favorite memories of living out here?

ETWhen my sister was born, I was three. I was in total shock that I had a baby sister moving into my house taking over my mother and father’s attention. How dare they have my sister without checking in with me? They said I was inconsolable. So they notified my grandparents on the phone and my grandfather came to get me. I stayed with Aunt Argie, Granddaddy Carter, and Granny Eva for the next three years out here on the farm—because I knew that I was special [laughs].

We did lots of things on the farm. We milked cows. We fed pigs and chickens. We helped plant the tobacco. I learned how to use a tobacco planting machine, which is a three-person operation. One person drives the horses, one person drives a tractor which pulls the tobacco planting machine, and then two people sit on the back. The machine digs a hole, squirts a quantity of water from the barrel which is part of the planting machine and you take a plant and stick it in the little hole. Then the machine covers up the hole as you move on. You get in the rhythm of the machine taking turns with your partner feeding the plants into the thing.That’s how we planted row after row of tobacco.

Kelsee Thomas

We learned to do a lot of things, but there were many things we didn’t learn. Somebody should have told us how to cut the chickens up because every Saturday my grandmother killed three or four chickens for Sunday dinner by chopping their heads off. We would help to pluck the chickens. Chickens go flopping around till they die, so my grandmother would dip them in hot water to loosen the feathers. And then us kids would take the feathers off and she would chop the heads off. She never showed us how to cut them up and do all of that. I still do not how to cut up a whole chicken.

I did go hunting with my grandfather. As a six year old, I wasn’t allowed to handle guns. But my grandfather would take me squirrel hunting with him, just the two of us. Those are good memories. In squirrel hunting, you have to be able to read all the animal signs. Okay, squirrels like hickory nuts. Here’s a hickory nut. Check out the area. There’s the scat and it’s fresh. So that means the squirrels are going to come back. After you read all the signs, you just sit and squat someplace till the squirrel comes back. I learned to be quiet, to be patient. You can’t be thrashing around, so I had to sit completely still and follow instructions. And then my grandfather would raise that gun and bring down the squirrel. He was an excellent shot. It was the same for quail and rabbits too. There were lots of free things in the trees. Berries and fruit. We had peaches, but we never really used the peaches in the yard because they always had worms in them. So my grandmother would order a bushel or two of peaches every summer so that she could can them for winter.

FTI remember lots of times with my great-grandfather (grandfather Carter), watching him train what he called bird dogs. To him, any dog he hunted with was a bird dog. He would stand in the yard on the other side of the farm—I can still picture him next to that big field—and he would have a fishing rod. On the end of the fishing rod would be a birdie, a lure, teaching the dog to retrieve.

I also have warm memories of walking with my great-grandfather in the woods here. Searching for squirrels, usually in the dusk just before the sun went down. Those were pretty amazing times when it was just the two of us and his dogs in the woods waiting for either a deer or something to wander by. There was no conversation between us, just two people sitting in the woods.

I remember feeling very protected, very safe when my great-grandfather would take me by the hand and walk with me in the woods. I remember making homemade ice cream from fruit that we had here on the farm. And in our prime we had a lot of different fruit—we had blackberries, blueberries, plums, peaches, pears, and several different types of apples. We had an orchard for all the fruit. I can remember hazelnuts, two different types of walnuts: Black walnuts and English walnuts. We had fruits, nuts, vegetables, and a river; we had pretty much everything we needed in this place. It was a very self-sufficient place.

“I feel much more at home around woods and water and places that are unbuilt. Living out here has been a great opportunity to build a home on land that not only my family had owned for a long time, but that I also have a personal connection to.” Frederick Tutman

COWhat has it meant for you to grow up in this place and to be a part of this rare show of longstanding Black land ownership? What is your hope for the next generation who carries on the property?

FTI feel a little guilty that we haven’t really kept up the orchards or the nut trees. There’s just not a lot of interest. I think there are only a handful of us in the family who are not only interested in keeping this place natural and rural but who also don’t mind doing the work to help that be the case. I don’t see much interest in this family in maintaining that kind of self-sufficiency. To me, being self-sufficient and not having to go to the store to get food is like being able to pick up a hammer and build something that’s useful without having to go and buy it off the shelf. It’s the ability to visualize something in your head and then build it. You don’t have to go and get permission.

It would be nice to come up with an operating plan and the resources needed to keep this place as an independent family farm. I’ve never had a vision for it being a big commercial enterprise, but really a family farm—one that maybe sells at least some of its product, but largely exists to benefit the family members. I think it’s kind of up to this generation to come up with that game plan. We have the experience, the backstory, and the history that comes with this place to be able to connect some of those dots.

etI feel a sense of stewardship, we should do whatever we can to make it productive. To show that it’s not neglected and that we do care. In reflecting on my life, all I can say is “wasn’t I lucky?”

CoMy hope is to be a part of that stewardship moving forward, to invest in the property and its upkeep in tribute to the four generations before me who called this place home and heart. That is my promise, and I look forward to working with my family to make this vision a reality in the years to come.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)