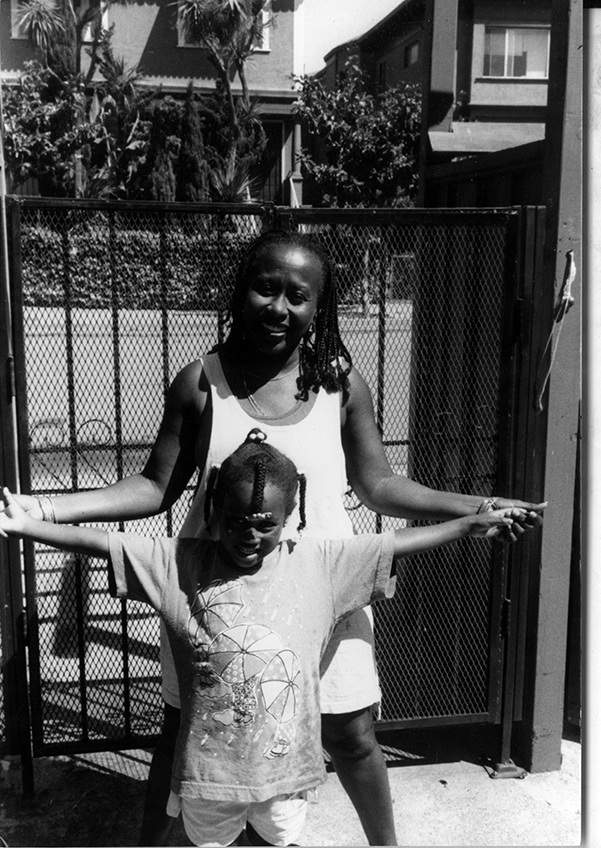

This contributed piece is a part of our Featured Voices series, which invites writers, poets, artists, and creators to explore the various intersections of Blackness and Greenness. Through “The Geographies I’m Made Of”, Teju Adisa Farrar charts her lived experiences in Oakland and Jamaica, connecting her personal history to the land histories of the places she calls home.

I was born on August 16, 1991 in San Francisco, California. At the time of my birth, Oakland—the first place I ever lived, was 43 percent Black. According to the last census in 2020, Oakland is now about 23 percent Black. But gentrification on this land started far earlier than the 21st century. Oakland is the unceded territory of the Ohlone, Chochenyo-speaking people. In 1400, they were the only people inhabiting the land that is now called Oakland. Before we were displaced and killed by police, they were displaced and killed by European colonialists. So, sometimes it’s hard for me to know which history to begin with. That’s why I decided to start with myself.

We all have relationships to our environment, and this is central to our human experience. We are part of the geographies surrounding us and simultaneously we impact the environments as we move through them. An environmental analysis of self reflects on the environments that we have experienced throughout our lives, how those environments have shaped our physical and mental realities, as well as how our perspective on nature has developed based on the aforementioned. This type of analysis allows us to explore how the social and political aspects of our environment interact with our personal experiences of it.

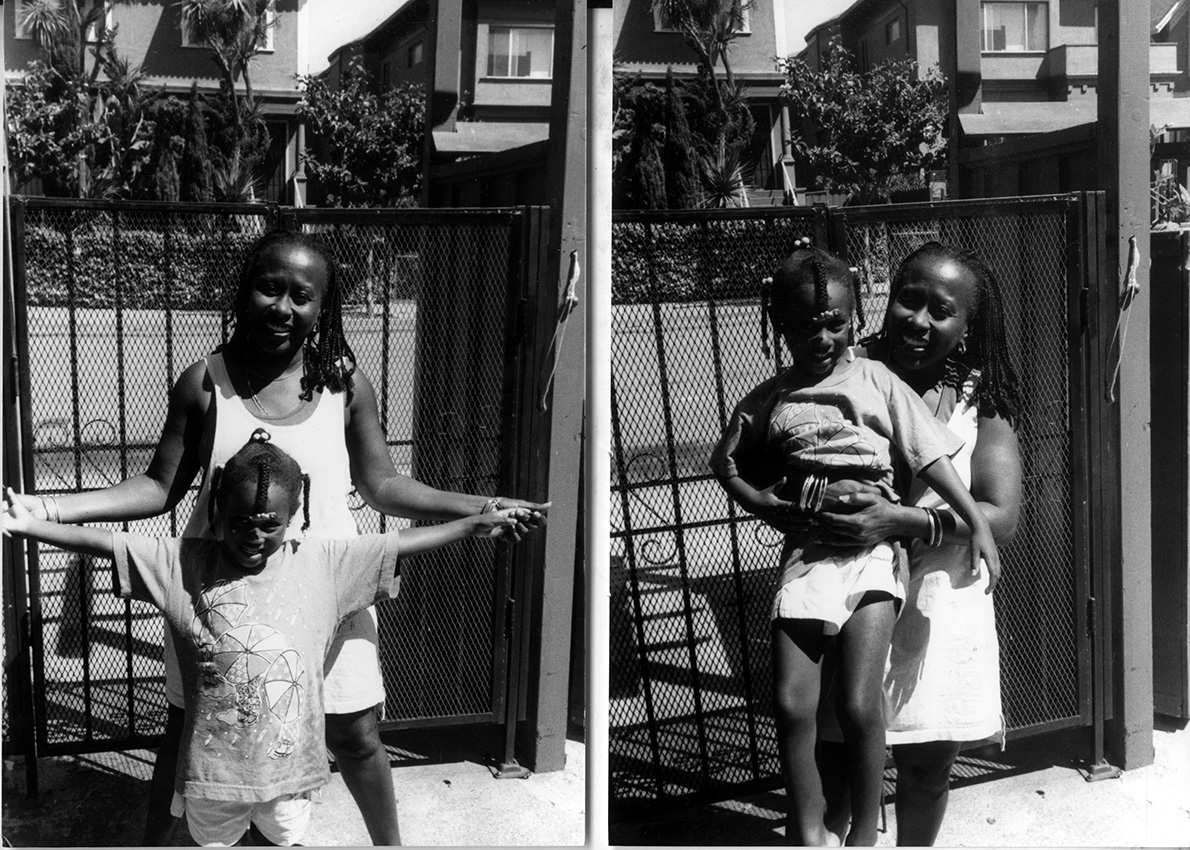

Positionality grounds us in the social and political contexts surrounding our identity. This spans race, class, gender, sexuality, privilege, and ability status. Positionality helps us articulate how differences in social position and power shape our access in society. It exposes how our identity influences, and potentially biases, our understanding of and outlook on the world. Positionality is a tool to analyze how we interact with and are impacted by our environment. The first two environments I have the most memories from growing up in are West Oakland, California and Spanish Town, Jamaica. Let’s start with the former, my hometown: Oakland, which some of us call “The Town.”

The first house I lived in was on 14th and Linden Street in a neighborhood called Acorn. I am recognizing and paying homage to the Ohlone people who have inhabited this land for centuries, have been stewards of it and harvested acorns, which are endemic to this area and much more sustainable than almonds. I’m from Acorn and although I call myself an Oakland native, I know whose land this is. Even though I haven’t lived in West Oakland for nineteen years, so much of my identity and current reality is connected to that place.

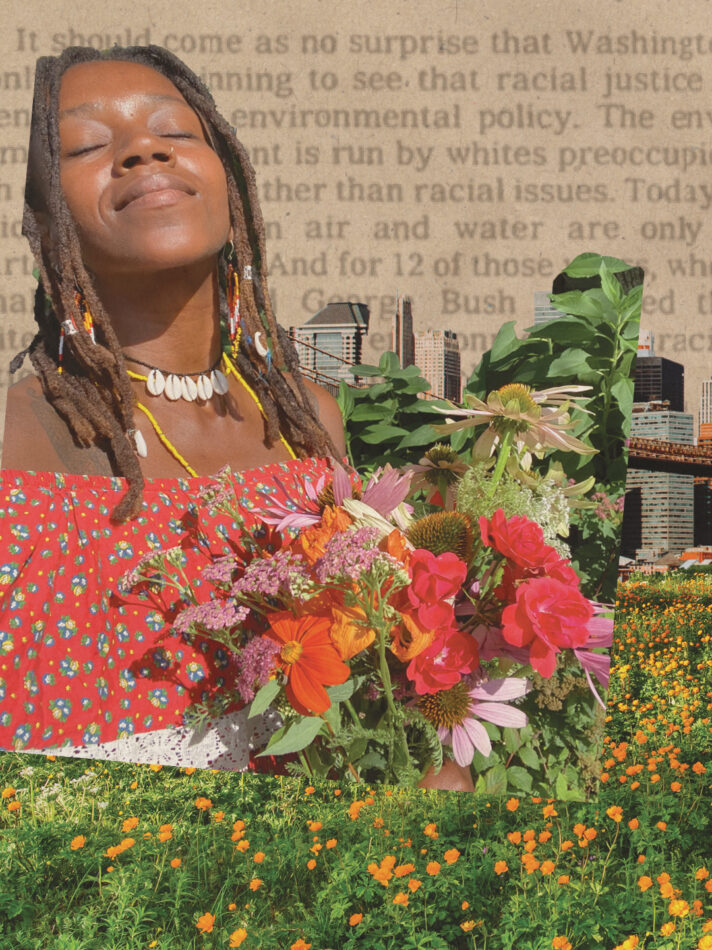

My brother and I both grew up with asthma. When I was young, children in West Oakland had asthma rates eight times higher than children in other neighborhoods. This is mainly due to pollution. West Oakland is situated between two major highways and adjacent to the port of Oakland, which creates a cloud of pollution. When I was a child there were no grocery stores at all in West Oakland—well before Mandela Grocery Cooperative opened up in 2009. West Oakland’s environment had been increasingly neglected since the1950s and 60s as an influx of thousands of Black people emigrated from the South to the West Coast for jobs during and after World War II. By 1960 more than 80 percent of all the Black people in Oakland lived in West Oakland. Thus, racism in Oakland was exercised environmentally. The Black Panthers combatted this economic and environmental neglect through self-organization, which is why their The Free Breakfast for School Children Program was started.

Community care is a form of environmental justice, especially when it comes to feeding children. From 1969 to 1980 the Black Panthers fed children breakfast in West Oakland every morning. In a US Senate hearing, the national School Lunch Program administrator admitted that the Black Panthers fed more poor school children than the State of California. The Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast program led to the expansion of the national School Breakfast Program by congress in 1975.

Thousands of children around the nation benefited from the Black Panthers caring for the children in their community whose environment was designed to keep them hungry.

As a child in the 90s, though my parents had the time and resources to go to grocery stores in other parts of Oakland and Berkeley to make sure we had fresh, organic food—I saw many children going to the corner stores to get something to eat before school. We also had a garden where my mother grew some herbs and other edible plants. Even within the same neighborhoods, our environments are not created equally . . . and in a place with very little access, I had much more than those around me. In addition to this, I had the added advantage of spending time in Jamaica; an island that still retained much of its nature and was run by Black people. Though it had—and still has—its own challenges and flaws that are part of a global legacy of environmental inequity that Black communities around the world experience.

My mother once said the story of our family in Jamaica was one of getting and losing land . . . but isn’t that the story of so many of us? And does the sea reclaiming the land count as us losing it?

Decades before I was born, my grandmother bought a house in Spanish Town, Jamaica after working as a secretary for a rum company for years. Spanish Town was the first capital of Jamaica until 1872, when the British moved the capital to Kingston after the Morant Bay Rebellion, contributing to the loss of Spanish Town’s economic vitality and development. Spanish Town is about fifteen miles west of Kingston and about twenty miles north of the nearest coast.

As a child, I vividly remember running around my grandma’s yard chasing chickens, playing with the dogs, and the time my mother made us pick up smushed mangoes that fell from the tree to take across the road for the cows. When I was a child we loved going to Hellshire Beach on the weekends. When there, we would get fresh snapper and festival (a sweet fried dough made with cornmeal and flour) from the fishing community whose livelihoods were connected to that beach and coastline. They would open a cooler of fish they caught that day and let us choose the ones we wanted to grill up. I still love the idea of being able to see and choose the fish I was going to eat with my family.

We can no longer go to Hellshire beach. The beach is disappearing. Climate change and Kingston’s harbor pollution has destroyed the coral reefs, allowing the waves to wash away the sand. This is exacerbated by sea level rise and hurricanes. Pretty soon, the fishing community there will no longer be able to make a living or even live there. It is one of the last few public beaches near Kingston, further decreasing access to the beautiful sea surrounding the island. Although days spent at Hellshire with my family will always sit fondly in my memory, I’m wondering how much loss I have to get used to. When I was in Jamaica this year, I was saddened by the amount of plastic pollution I saw on the beaches, even though plastic is technically banned in Jamaica. Unfortunately, Jamaica has not been able to prevent products being wrapped in plastic when they are imported. So while Black folks in Cancer Alley in St. James Parish, Louisiana suffer from pollution from petrochemical plants, Jamaica’s landscape is deteriorating due to plastic pollution from the products these petrochemical plants manufacture. We are all losing something whether it’s our health, our land, or our memories.

Displacement due to gentrification and displacement due to climate change are both created from legacies of colonialism, segregation, and environmental inequity. These historical structures continue to shape the current realities that we are all living through. All of us have environmental footprints . . . imprints that start well before we are born, are passed on through lineage and carry our future generations’ paths. We cannot understand our future possibilities if we do not understand our present circumstances, which are predicated on personal and political histories. Looking at our own environmental biographies gives us a deeper understanding of what we are losing to these unsustainable systems, the healing necessary to survive, and the interactions with nature that make us who we are today.

—

Teju Adisa-Farrar is a Jamaican-American writer, geographer, facilitator, speaker, researcher, and poet from Oakland. For over a decade, Teju has worked to connect the dots between environmental, cultural, ecological, and urban issues. She spends her time consulting with progressive organizations, facilitating intersectional conversations, supporting community initiatives, working on creative projects, and giving talks on urgent topics. Teju is based between Lenape Land (Brooklyn, New York) and Ohlone Land (Oakland, California).

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)