This story was originally published in the first issue of Radicle, our interactive print publication which centers Black voices and perspectives in sustainability and the environment. Radicle explores a range of topics including environmental justice, indigeneity, sustainable homebuilding, and plant-forward home cooking. The publication was designed to spark curiosity and celebrate community, all while healing our people and the planet.

Land has always been important, but the relationship with it has always been complicated for my family. My ancestors were sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta. For generations my family worked land they knew, but could never own.

We begin the UNEARTHED series by featuring Maria Pettis, University of California, Berkeley PhD student in Geography, who reflects on the importance of environmental justice, geographies of Blackness, and family land histories both past and present. Maria and I met through our undergraduate studies in Environmental Analysis at Pomona College, finding commonality in our natural curiosity for the world around us. Now years into a rich friendship, we remain connected by our shared determination to find sanctuary and justice in the environment.

Nia What is your personal connection to the land?

Maria I feel like the land and I are interdependent. Like my ancestors, I carry it with me and it shapes how I understand, sense, and navigate the world. Thinking about my connection to land, I realize that the land presents itself in my dreams, often more than anything else. I see spaces where I have been, views of my old neighborhood in Frog Island from the perspective of my five-year-old self. When I find myself off-balance, I notice that the spaces and environments I am in are also off-balance. Working with the land, in my garden or in green spaces, helps me find balance. It also gives me joy. My favorite thing is to just sit still and watch everything around me. I think that is why I ended up studying ecology and then geography. It gave me the opportunity and legitimacy to just be outside and observe plants, animals, insects, and people. When you’re still, or for me, just sitting near flowering plants watching solitary bees do their thing, you realize that the land and everything in and on the land are constantly in motion. The Earth consists of so many worlds across scales, really, we are just small things that are part of something so much larger.

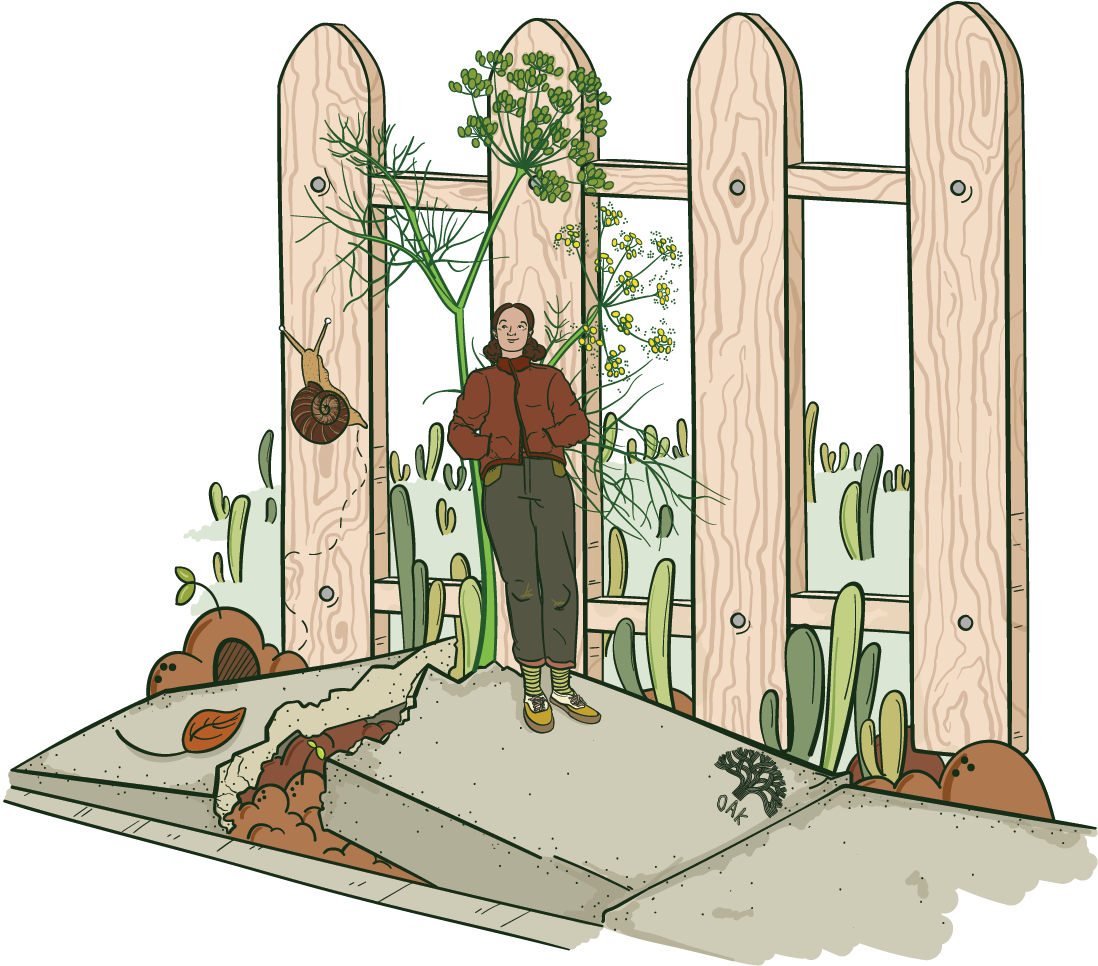

Aside from observation, I interact with land in a very tactile and embodied way. I love to run my hands through grass and feel different textures. I am constantly looking and smelling for aromatic plants or for different tastes. In West Oakland where I live now, while much of the land is paved over, I am constantly finding fennel and raspberries sprouting through cracks in the pavement.

“Blackness is often framed as un-geographic, as drifting and out of place, or only in the context of ceaseless labor. But these narratives exclude all of the other stories, the interdependencies, and relationships that I know also exist.” Maria Pettis

Nia What is your family’s land history?

Maria I come from people who have always gardened. Both of my grandfathers cultivated huge vegetable plots to feed their families. I still remember the taste of my grandfather’s tomatoes that he grew in rich black soil next to a canal feeding into the Illinois river. It’s nothing like what you can buy in stores. I also remember my other granddad growing cucumbers in a guerrilla garden at the end of our street in Frog Island. My granddad, my father, and I still make pickles from homegrown cucumbers.

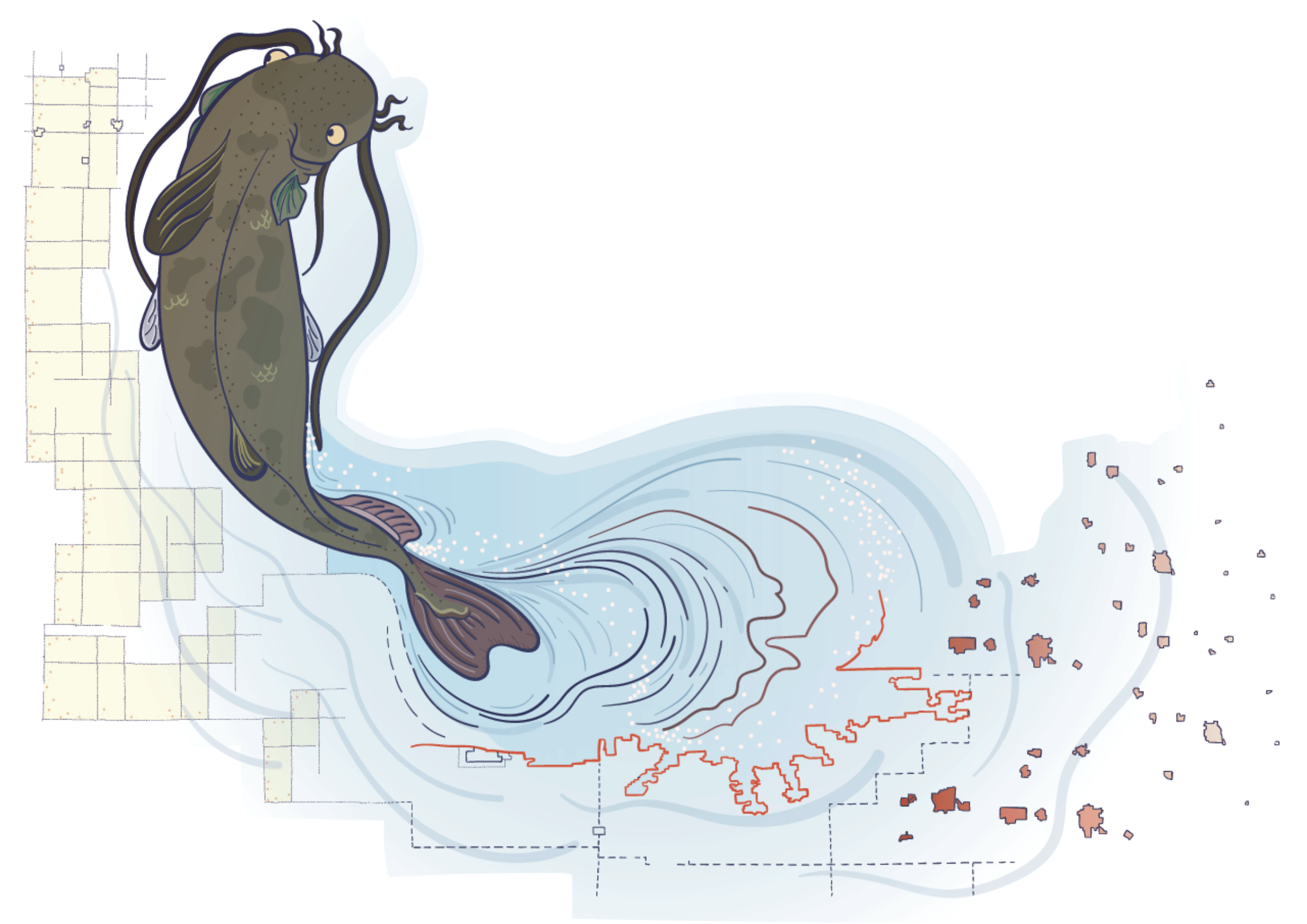

Land has always been important, but the relationship with it has always been complicated for my family. My ancestors were sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta. For generations my family worked land they knew, but could never own. My people have always been river and lake people. My granddad whose nickname is “Bean,” was the first in his family to migrate north and make new life in Chicagoland in the late 1950s. We still have family spread out in places like McGehee, Arkansas and Tunica, Mississippi. The ironic thing is that my granddad left the swamp land and flood planes of the Mississippi River Delta, but the only place he was allowed to get a mortgage and build his home was also in swamp land in Waukegan, Illinois. The first house I lived in was across the street from where my granddad built his. Beneath the street runs a creek, now channeled through a subterranean tunnel. Every few years when there are heavy rains, the creek, the street, and basements flood. You have to take your shoes off to wade through ankle-deep water. I remember seeing big catfish navigate the tunnel and water that feed into Lake Michigan. It is said that the sound of frogs is how the neighborhood got its name.

Plantation slavery, dispossession, segregation, and redlining shape the geographies of my family. I think a lot about the history of Blackness and the relationship to land in the United States. Blackness is often framed as un-geographic, as drifting and out of place, or only in the context of ceaseless labor. But these narratives exclude all of the other stories, the interdependencies, and relationships that I know also exist. My family, for instance, holds catfish and fishing as almost sacred. It is our staple food, and the process of fishing is also a way of engendering stillness, observing, and knowing land and water. My Great Aunt Mary, who is now in her 80s, is still an avid fisher. She creeps around her yard in early morning with a flashlight collecting nightcrawlers, the huge worms that inhabit rich northern Illinois soils. She also grows plums and strawberries in a plot next to her house. When I visited her last, I helped her weed this plant called Creeping Charlie. She joked that her favorite thing to do these days is to sort through the things in the grass. My granddad, also in his 80s, gets up almost every morning and walks through the forest preserve near his home. I think it gives him peace of mind and energy.

Land for my family has always been symbolic of fostering life. Great Aunt Mary told me that during the Great Depression many Black people who were sharecroppers in the Delta were fine, but it was the landless people in the cities who were struggling. For Black people who worked the land, you grew everything you needed. The land provided for us and we were okay.

Nia What practices are a part of your daily life that affirm your own land history? Can you share some recipes, gardening tips, hair products?

Maria I tend and plant herbs in my yard. I take food as medicine, so I cook with what I grow—thyme being my favorite. I also just love to wander around and explore parks with my dogs. When I return home to Waukegan, one of the first things I do is survey our family garden and the potted blueberries I gifted my mother. I also explore the ravines near our home and make mental maps of spaces and places almost ready to harvest. Spring in Illinois is when lilies of the valley pop up. Summer in Illinois means mulberry picking and fall means tart wild grapes that grow in the brush along fences near the beach, and stink bombs, the green fruits of a black walnut tree that drop into our yard. Black walnut can treat things like ringworm, and soaking the fruits in water is a natural weed-suppressing tea. The nuts separated and dried from the green fruits can be shelled and used for baking. It’s a magic plant of many uses.

I relocated to the Bay Area a year ago. One of my favorite things to do is continue this practice of walking, knowing, and mentally mapping land and spaces here. Where I live now, much of the soil is covered by concrete, but I am always surprised to find plants that have many ethnobotanical uses. Herbs like rosemary also grow huge, woody, and bush-like here, where in Illinois they are mostly annuals.

Aside from edible plants, I make a lot of tea-like herbal decoctions and drinks, and self-care products for myself and my family. Ginger, turmeric, a pinch of cayenne, and black pepper help ward off sadness—it’s my favorite spicy tea. Shea butter and castor oil with mint, does wonders for your skin and has natural SPF. The best thing lately has been a divestment from store-bought conditioners. I have natural hair, and have spent years and probably thousands of dollars on expensive and ineffective conditioners, leave-ins, and hair products. The plastic is wasteful, and I swear it’s just a way of charging Black people more for something that gets washed down the drain every week. I now make my own flaxseed gel conditioner. It is pretty easy and cheap to do. I boil about 1/3 cup of flax seeds in 3 cups of water, then I add castor oil and some essential oil, and then strain it through a nylon. You have to refrigerate the jar, but it lasts two and half to three weeks, and my curls are popping!

Another favorite recipe is homemade face wash powder, made from ground oatmeal, bentonite clay, ground almonds, spices, and essential oils. It smells amazing, soothes, and lightly exfoliates my skin.

Nia What does it look like for you to pass on your own land histories?

Maria I like to engage children, my peers, and young people in adventures on land. I think it’s important to explore and to learn with all of our senses. I do love to touch things and try to share this experience and little snippets of things I know with friends and family. I try to bring people and their attention to special places I find and model how to be with land in a mutually reciprocal way. It’s kind of cool to take walks with people, stop and say, “look this is mint—smell this,” or “here is oregano, rosemary, thyme, sage.” I think we learn these things through experience and it’s important to share these opportunities with others. I also think it is critical to learn from elders, and to learn about the histories of people whose ancestors have lived in places we now inhabit. Honoring and respecting Indigenous land histories are critical.

Nia In what ways do you think people of color can affirm their land histories?

Maria I think for people of color, Black people especially, we can affirm land and history by getting in it—getting to know the places we live, at different scales, micro to macro, and understanding how and why we have come to be in these places. I am against neoliberal and white environmental narratives, which often exclude and enclose land and public space from Black and Indigenous people and assert myths of purity and preservation for some places and the degradation of others. What if we thought of and treated all land with respect and mutual care? The land of our homes, neighborhoods, and streets is just as important as the land of regulated parks.

In my neighborhood in Oakland now, the nights are lit up by huge, invasive streetlights. They make the night seem like daytime. It’s strange. We can’t see the stars, just these lights we try to block out with blackout curtains. The history of these lights, that you would never see in majority white neighborhoods or Oakland Hills, is enmeshed in techniques of surveillance and control of Black communities. But these lights and the practices of paving everything, affect the lives of people and everything else that lives on the land here. In this sense, I think we have to collectively fight to protect and care for ourselves, which includes the lands we live on.

“I think we have to collectively fight to protect and care for ourselves, which includes the lands we live on.” Maria Pettis

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)