Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

If you’ve ever stood atop a mountain ridge, overlooking the plentiful treescapes of Appalachian wilderness, or summited a mountain on the West Coast, then perhaps you’ve felt the power of these spectacular giants. Their height alone makes one ponder the existence of a higher power. It is in the presence of these geological creations that we can learn so much about our own history. The Rockies, Smokies, and Blue Ridge are all part of the gorgeous mountain range that is Appalachia. These vast vertical stretches of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rock are geological curiosity and sources of untold Black history.

Mountains are a marvel millions of years in the making. Some of the largest mountain ranges we know today were created by the collision of tectonic plates (the masses of Earth that slowly float on the liquid mantle underneath Earth’s crust). These plates are the reason we have earthquakes, volcanoes, and other geographic structures. But mountains are intriguing both for their geography and the life that thrives in their highest reaches. These habitats are diverse, wild, and, at times, dangerous. The plants and animals that survive in these extreme conditions are resilient in their ability to scale sheer cliffs, exist in below-freezing weather, and even subsist amongst the thin atmosphere, proving they are just as resilient as the mountain rocks themselves.

The Appalachian mountains are the oldest mountain range in North America. The shifting of the American and the African tectonic plates resulted in a collision known as the Appalachian Orogeny, which forms a pointed wedge of sharp rock that extends as far north as modern-day New York and reaches down to modern-day Mississippi. Over the course of 270 million years, weather, wind, and ocean waves beat this wedge into the soft hills, tree-covered ridges, and swaths of biodiverse landscape we know today as Appalachia. In addition to being filled with wide arrays of resilient plants and animals, this region is also home to a lesser-known diversity—one that is often overshadowed by the narrative of Appalachia as a community of poor White mountaineers.

EARLY SETTLEMENT AND THE SECOND KINGDOM

Appalachia is a small giant. Ecologically speaking, it contains the highest amount of endemic plant and animal species in North America. The collision that created the Appalachian mountain range placed so much pressure and heat on the rocks, that it transformed the organic matter that existed between the tectonic plates hundreds of millions of years ago (old bogs and dead animals) into a literal mountain of coal. This coal has powered the country for over a century. The geological diversity of the region from limestone and karst cave formations to deciduous forests and bubbling river ecosystems, present a number of habitat types for an even more diverse collection of vertebrate and invertebrate species.

Pre-colonization, the Cherokee called Appalachia home, often sharing the landscape with members of the Iroquois, Powhatan, and Shawnee peoples. As colonizers came through, claiming the landscape and forcing these tribes westward and stripping them of their homelands and regional foundations, they brought with them enslaved Africans whose traditions, music, and food meshed with Cherokee practices to form the backbone of modern-day Appalachian culture. In North Carolina’s Appalachian range, enslaved Africans spent their lives on small farms in the fertile mountain valleys of the region, introducing melons, okra, peanuts, yams, and medicinal herbs to the landscape.

In the Catoctin Mountains on the easternmost part of the Blueridge mountains in Northern Virginia, many enslaved Black people brought the much sought-after knowledge of ironworking from Africa, launching Appalachia into a base for the American iron industry. And perhaps one of the most famous contributions of African Americans to Appalachian culture is bluegrass music and the creation of the five-string banjo, thought to be inspired by West African hide-covered string instruments such as the ngoni and the xalam.

Oftentimes, in Appalachia, poor White Scottish-Irish populations settled closely with free Black and Indigenous populations, a relationship which gave rise to Appalachia’s Melungeon multiracial communities. The most notable instance of this multi-racial cohabitation took place during the Civil War as many residents in now West Virginia split off from Virginia when the state seceded from the Union. This region served as an active path on the Underground Railroad running from Northern Tennessee to Pennsylvania. And when enslaved Africans were emancipated in the early 1800s, they often settled among the mountain ranges in free farm communities separate from White settlers. One such community was the Second Kingdom or the Kingdom of the Happy Land in Western North Carolina.

In the hysteria and violence following the Civil War, newly freed Black people often traveled North from Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina in search of a peaceful paradise among the mountain ranges. They made their way toward what is modern-day Tuxedo, North Carolina to form the Kingdom of the Happy Land. In the years following, the community grew rapidly, housing between 200 to 400 people who were governed by a monarchy and an independent treasury. The community grew its own food and made money selling medicinal treatments to nearby towns. That money was then saved to purchase the land they’d settled on and protect them from turning to sharecropping. Many of the members of the Cherokee Nation who had been displaced due to colonial settlement and the Indian Removal Act also found refuge in the Second Kingdom, contributing to the culture of the settlement and traditional practices used to farm the land.

Near the start of the 18th century, development threatened the prosperity of the community, and residents began moving away to neighboring towns. By 1900, very few residents remained, and the stories of this land were lost to the remaining residents and the mountains of Appalachia.

Civil Rights in Appalachia

As these narratives of prosperous Black settlements were fragmented through time, the Appalachian experience became a narrative of “pristine wilderness.” In 1926, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established, and Shenandoah National Park followed in 1935. And the roads, paths, and famous structures like Clingmans Dome, the highest point of the Smoky Mountains, were built with the underpaid labor of Black Americans.

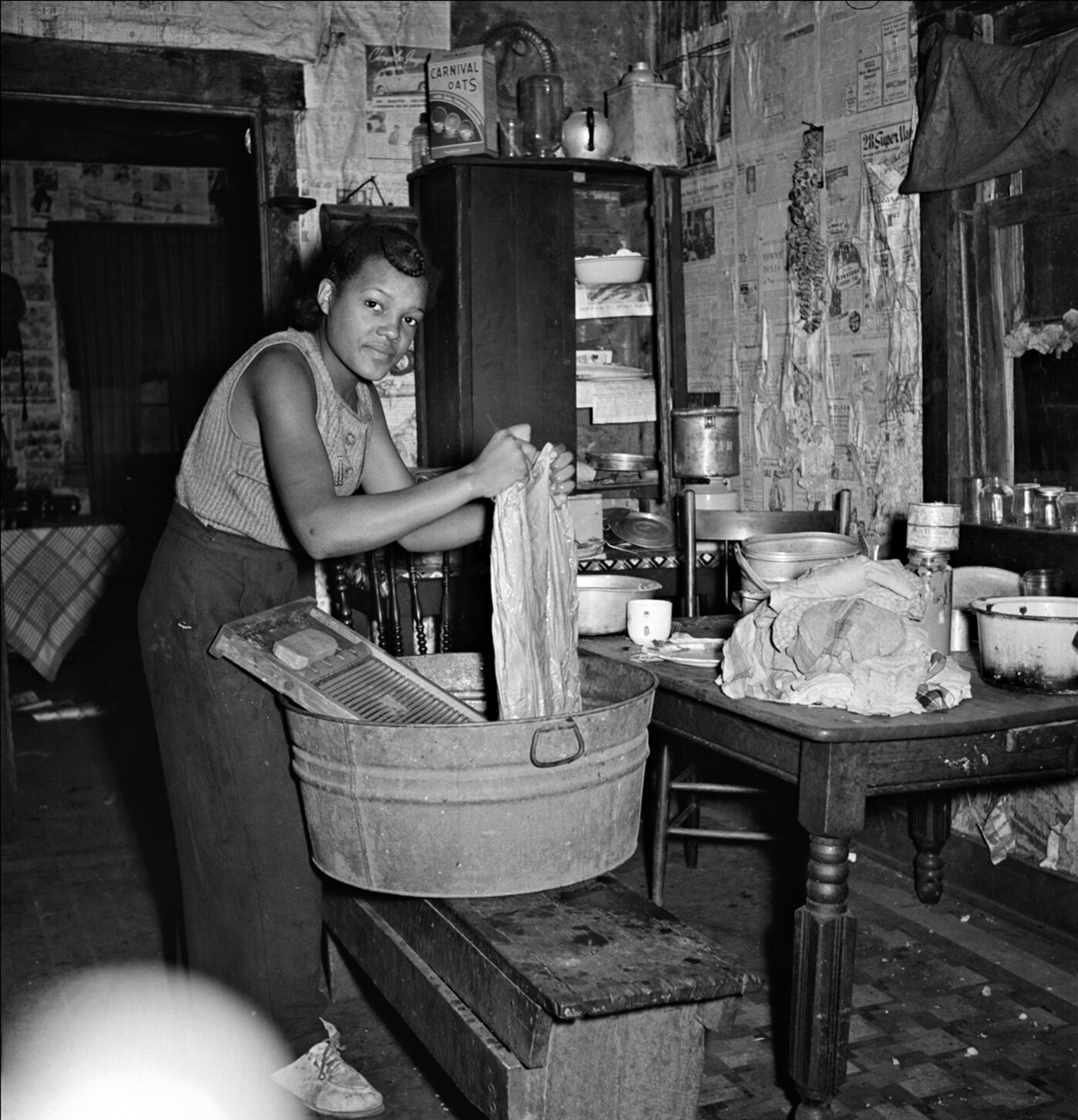

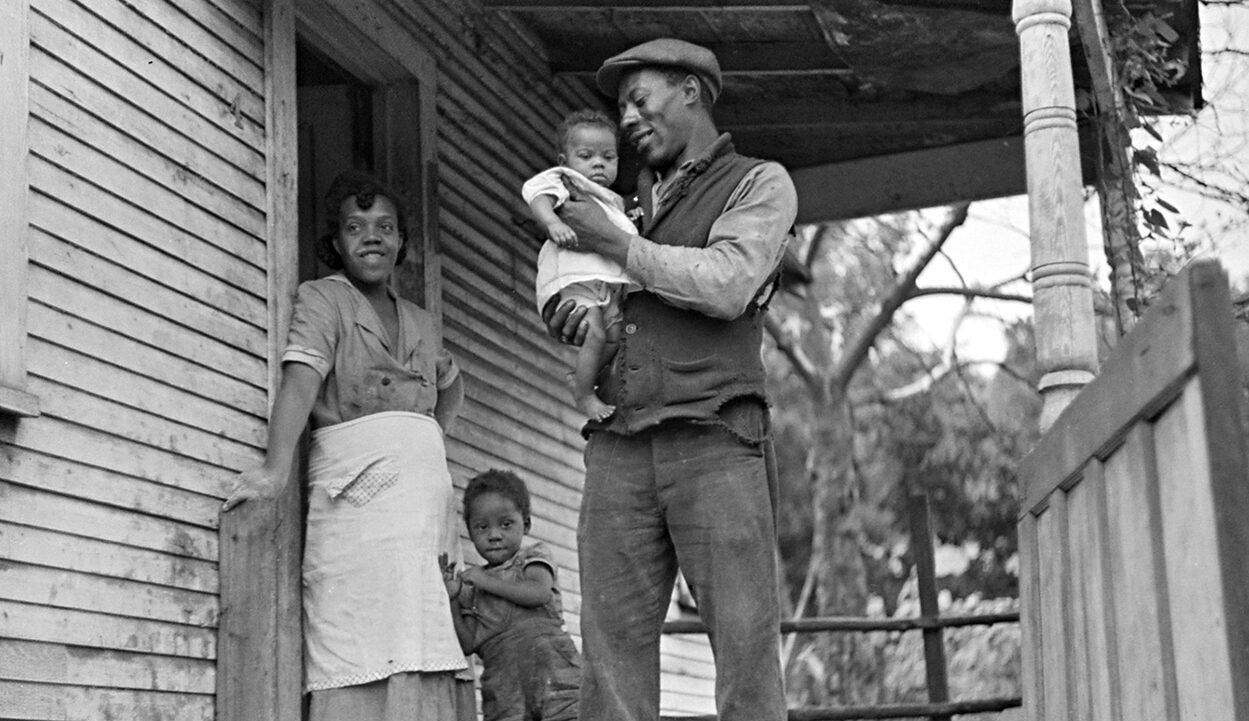

The region also became a centerpiece in President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty with a more specific focus on water, electricity, and wealth access for Appalachia’s White populations. Appalachia was and continues to be known for its White working class, coal miners, and loggers who paint a picture of hard work and living off the land. That long-standing narrative whitewashed the diversity of the region and often left Black and Brown voices and their needs out of critical infrastructure development and welfare.

In North Carolina’s Appalachian range, enslaved Africans spent their lives on small farms in the fertile mountain valleys of the region, introducing melons, okra, peanuts, yams, and medicinal herbs to the landscape.

People like Mary Rice Farris from the mountains of Kentucky refused to take that discrimination lying down. A farmworker, maid, and saleslady by day, Farris grew her political power by serving a variety of roles at the First Baptist Church of the City of Berea and as vice president of Church Women of Madison County. Farris grew her political prominence in Madison County as an area coordinator for the Republican Party of Madison, and went toe-to-toe with White Kentucky politicians. In a 1967 application for a position with the War on Poverty program Farris wrote: “All my life I’ve done political and community work. The people have been deprived of what they should have received, and I would like to see that something is done for them.”

The following year, Farris went head-to-head with Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Congressman Carl Perkins, when they visited eastern Kentucky on Kennedy’s eight-stop tour of the region. Farris arrived at a school building in Vortex, Kentucky where the tour was speaking with local Appalachians, and entered a room full of poor White Appalachians to tell the story of Black Appalachia.

“[Why are we] spending $70 million dollars a day in Vietnam, plus loss of life, when [there] are millions of people in our area hungry, without homes and decent housing, or without clothing,” she said. “And we would also like to know why the Negro is having to fight for a decent place in society as a rightful citizen? Why we, as American Negroes, are having to fight and speak out for a right to take decent responsibility in this great nation?”

Farris left Kennedy and Perkins stumbling with empty sentiments and continued to spend the rest of her life pushing for equal access to public services, education, and resources for Appalachia’s Black residents.

Whether in the Western Rockies or the Appalachian Mountains, Black narratives have been left out of discussions of wilderness, conservation, and mountainous living. These stories have not only been erased with regard to the prosperity and beauty of these landscapes, but the struggles, poverty, and hardship of life among the mountains has excluded Black lives and experiences by painting the experience as an act of White resilience.

Today, we reflect on the pure power and majesty of these mountain ranges of Appalachia, as something inextricably bound to Black resilience, Black freedom, and Black community. We see this in stories like that of Ms. Sheila and her son John Paul Castells, who have built a life for themselves in the rural corners of the Appalachian wilderness with the resilience and force like that of Mary Rice Farris. All three of them took their wellbeing into their own hands—matching the strength and inherent diversity of the mountain ranges themselves.

Feature Image Photo Description: A Coal miner, his wife and two of their children in Bertha Hill, West Virginia, September 1938. Marion Post Wolcott / Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Photograph Collection Library of Congress

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)