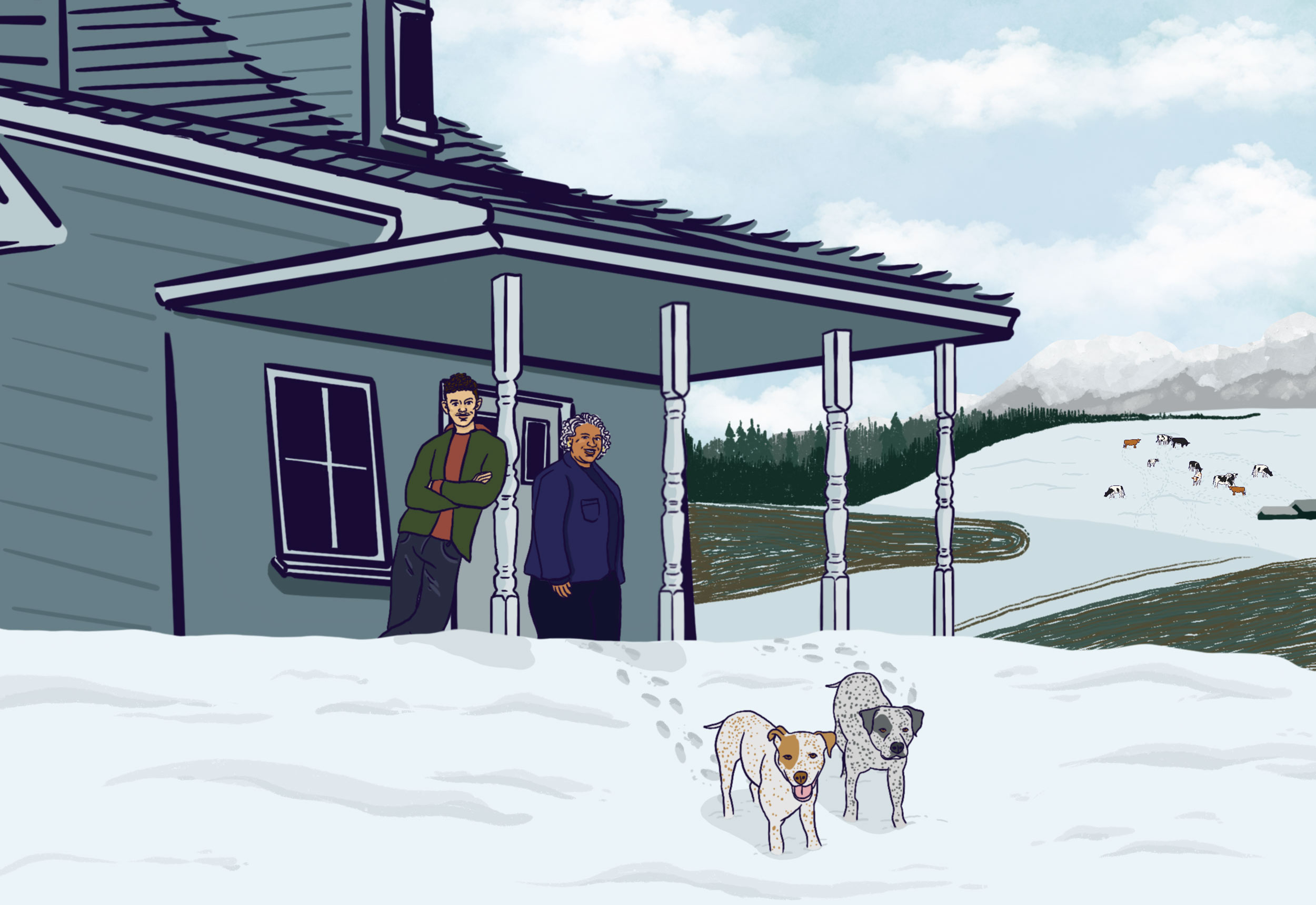

In May 2020, the Earth in Color Editorial Team spoke with Ms. Sheila Coleman Castells and her son John Paul “JP” Castells about their life as a Black family living in rural West Virginia. Sitting side by side on Zoom, they invited us into their home and gave us a taste of their world—sharing their family’s ancestral legacy of living with and off of the land.

Ms. Sheila and JP’s intergenerational dialogue allows us a window into rural Appalachian life, where chosen community, sustainability as an ancestral practice, and synergy with the land and water is held at the center. Their story encourages us to imagine the possibilities that appear with moving from an urban city to a rural space, and beyond that, how we can inspire curiosity and daily communion between ourselves and the land, regardless of our physical location.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Earth in color Can you introduce yourselves and give us a sense of where you all are sitting right now?

Ms. Sheila My name is Sheila Coleman Castells. I’m originally from Washington, DC and for the last fourteen years, I’ve lived in Eglon, West Virginia. I own a small lobbying and advocacy firm that works in West Virginia, North Carolina, and DC. JP is my son and only child.

We live in Eglon, West Virginia, in Preston County, right on the western border of Appalachian Maryland. We’re mostly a farming community; Eglon is not a formal city, and it’s so rural that we have no street lights, only two stoplights, and most of our roads are made of gravel. In the last census, our town had about 180 people. It’s a very high, mountainous area—in fact, I call my land the Holy Mountain.

JP I’m John Paul Castells, or JP. I am a senior at Bowdoin College as an English major. I’m a writer and a poet, and I also love working in restaurants.

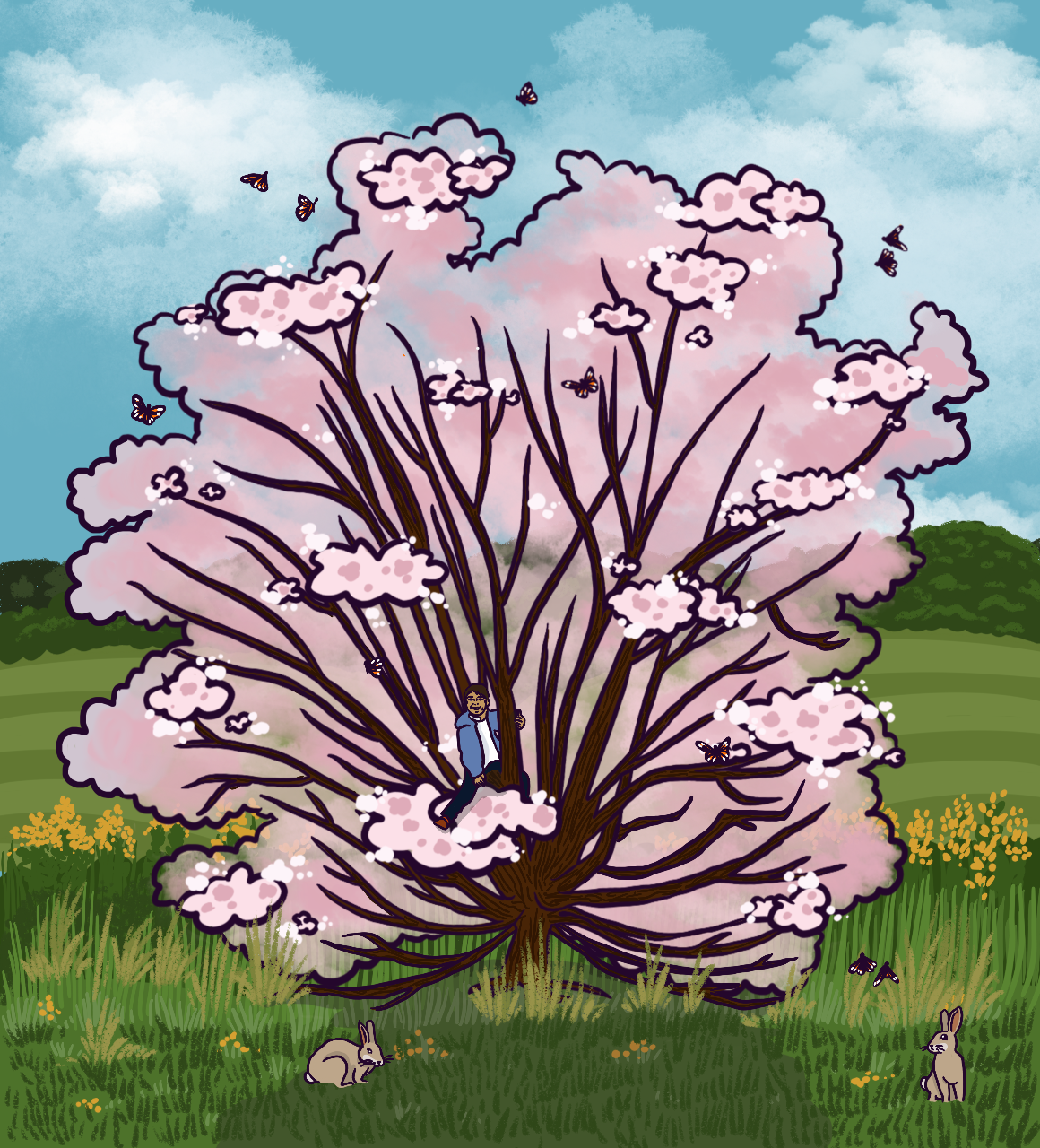

From our porch, I can see the mountain ranges that my friends live in and the mountain my high school is on. We have three acres of land with hardly any trees, except for one big cherry tree in the back—a big grandmother tree with branches that lay on the ground, almost like it wants to scoop you up and hold you in its arms. We mow most of the lawn, but the rest of it, we leave to preserve the normal habitat, so snakes, field mice, and butterflies live and cocoon in it.

earth in color At Earth in Color, we define land history as memories, family stories, recipes, personal connections to the land, and how our relationship to a specific place shapes our character. How do you define your land history, and where do you call home?

Ms SheilaWhen I think of the concept of land history, I can’t help but think of my past, and not just what I’ve acquired, but what I’ve lost. I was born in Berkeley, California, but at two weeks old, I was shipped out to DC, and grew up there about two miles from the Capitol. My father worked on the railroad and then as a chef, first in New York, and then in DC at the House of Representatives restaurant. We were one of those families like in the movie, The Butler, we worked in service to the White elite of this country, but our heart was in our land in Virginia.

My father was from Brunswick County, Virginia, and he grew up on a farm that his family had owned since Emancipation. His family was mixed race, and his father, my grandfather, inherited the land with his eleven siblings. We went down there five or six times a year. A lot of Black folks have that experience of going back to the country; you send the children down South for summer vacation. Growing up, I spent most of my summers in Virginia. My connection to our historic land in Virginia belongs to both sides of my family—not just my father, but my mother’s heritage is also in that same county. It was my grandmother’s heritage. They weren’t from the same family, but they knew each other. Our history goes all over the United States, but it all comes back to Brunswick County, Virginia.

“When you love the place that you’re in, you remember almost everything about it.” JP Castells

JP When you love the place that you’re in, you remember almost everything about it. I was born in DC, but I claim West Virginia as my home. I came up here every other weekend until the eighth grade, when I moved to live with my mother. When I try to think back on my childhood in DC, I can’t remember a damn thing. And yet, from high school onward, I can clearly remember everything about living here. I remember drinking the water for the first time and thinking they’d put sugar in it, it was so clear. I can remember every birthday party that I had here—where I ran in cornfields, unafraid to get ticks all on me, or of the snakes and other critters.

As an only child I would be told, “Don’t go where I can’t see you.” Luckily, on a hill where you can see just about everything, I could go almost anywhere I wanted. No matter what the season was, I was always outside. I loved the quiet and the peace. I felt connected to something bigger than myself, in both my community and in my aloneness.

Earth in color What led you to leave the city for West Virgina?

Ms. Sheila ome until my parents were ill, and I had to make a very tough decision to sell our family home so that I could provide for them. I don’t think that anybody really knows what their old age is going to be like. As African Americans, we haven’t had the ability to plan for that—because of redlining and insurance; because we’ve never made that much money to be able to put away for a long, old age.

After I sold the house, I had to consider what I wanted for my life and for my little boy. JP was not going to be tough and rough in the neighborhood; he was a kid who wanted to run outside, play in the snow, draw, do Boy Scouts, and write poetry. On the weekends, we’d leave DC to stay at one of the state lodges or rent a cabin in West Virginia, an hour or so from DC. Nothing made JP happier than to play with worms in the mountain soil of West Virginia. I knew the kind of kid I had in front of me, and I did not see a way for me to give to him—a loving, sensitive little boy—what I thought he should have in urban DC. I very much wanted him to be raised where he was happiest, and with a sense of infinite possibilities.

earth in color How did you find the Holy Mountain?

ms. Sheila In 2004, Hurricane Isabel came up the East Coast and hit DC. We were out of power for seven days, and my son was staying with his father at the time. During the hurricane, I dreamed that I was carrying my son up a mountain in the rain, under a big black umbrella. All I could hear was a voice saying to me, the scripture invocation to “get thee up into the high mountains.” I finally made it to the top of that high mountain, and there on top of a hill, I saw a house sitting in the sunshine. I realized that that was our house; I walked in and we were safe.

“During the hurricane, I dreamed that I was carrying my son up a mountain in the rain, under a big black umbrella. All I could hear was a voice saying to me, the scripture invocation to “get thee up into the high mountains.” I finally made it to the top of that high mountain, and there on top of a hill, I saw a house sitting in the sunshine. I realized that that was our house; I walked in and we were safe.” Ms. Sheila Castells

That dream haunted me. The next year, we decided to come to West Virginia for my son’s spring break. When the lodge we wanted was full, we set off for the Blackwater Falls Lodge for the first time, not knowing that it was 4,000 feet above sea level, and that there was a snowstorm. It was a terrible trip, but we made it. We went to sleep exhausted, but the next morning, we went outside and it looked like a winter wonderland. We saw Blackwater Canyon, which is magnificent and unlike anything you’ve ever seen. It’s hard for me to imagine that one denies the majesty of God when you look at something like that—man did not create that.

The first person we met at Blackwater Falls was a French woman and real estate broker named Annie. Annie walked up to me and immediately prophesied that she would give me my house. I didn’t believe her; I had just bought our house in DC, but a year later, on New Year’s Day 2006, she called me and said, “Sheila, I have your house.” I didn’t understand, but we made the day trip there. The last stretch was this long, unpaved mountain road, and at the top of that mountain was the house that I had seen in my dream. I found myself writing a $2,500 check to put down on this house that day—even though we already had a house! I didn’t know how I was going to afford two houses. But I believe in the power of my dreams. I believe in the power of trusting when something feels right deep inside.

“I believe in the power of my dreams. I believe in the power of trusting when something feels right deep inside.” Ms. Sheila Castells

Earth In color Going back to your childhood in Brunswick County, Virginia. What did you all grow on the land? What are some practices you’ve carried with you today?

Ms. Sheila Our farm in Virginia raised some vegetables, but mostly tobacco. That was the cash crop, and that tobacco money put my aunts through college. My people were able to leverage their own land toward the education of their children because food was not an issue for us. We were baking bread, canning tomatoes, making sauces, jam, and preserves. We froze and cured meats at home; we’d start curing ham in September so that it would be ready by Thanksgiving. In the summertime, my family canned things—peaches, pears, berries, and corn—so that in the wintertime, we had everything we needed.

In DC, my parents always got our meat from butchers who would trim the meat right in front of you, and real fishmongers who brought in the day’s catch. When I was in graduate school, I lived in Nelson County, Virginia on top of a mountain, and I bought my food from my neighbors there. I realized I had a whole culture around me who valued that.

Food is such a part of my family’s life, from our profession to a connection with our history, to the way we connect with each other. Our clothes may have been shabby, and our car might have been a hoopty, but we had food. We had beans and whatever we needed; we had charcoal because we were constantly grilling—we knew how to survive.

earth in color How does this deep-seated value for community-oriented cooperative living show up in your lives today?

Ms. Sheila Like in Brunswick County, Virginia and Charlottesville, Virginia, where I went to graduate school, on the Holy Mountain we get our meat and vegetables from our neighbors who live within a five-mile radius. A guy delivers our eggs to our porch; we buy cheeses and produce from the Amish, and participate in Community-supported Agriculture (CSAs) and other cooperatives. I know where my food has been; we can see it and name it.

“A guy delivers our eggs to our porch; we buy cheeses and produce from the Amish, and participate in Community-supported Agriculture (CSAs) and other cooperatives. I know where my food has been; we can see it and name it.” Ms. Sheila Castells

We contribute to our economy directly, and that means a great deal to me after having lived through Hurricane Isabel where even the grocery store was closed because it had no power. There is no health or wellness without good food. Food is health. Food is culture. Food is connection to other people.

There’s so much of that natural bounty here that is normal to us: Fiddlehead ferns, cranberries, Panax ginseng, and ramps (a spring onion). Ramps will sometimes go for twenty dollars a pound at a place like Whole Foods or Wild Oats, and foodies that frequent Whole Foods or, like me, subscribe to The New York Times cooking section might see these ingredients as trendy. When I saw a recipe with ramps in the The New York Times cooking session, I thought, “That was great, but damn, I’m down here and you steal our natural bounty because you think it’s trendy when that’s our normal.” People who don’t own any land will show up and steal our produce, and because they don’t have the knowledge, they don’t harvest sustainably and end up damaging our culture. People who have been able to pick ramps and other produce out of their backyard for centuries off of virgin land can’t do that when people take them unsustainably.

earth in color How has your connection to the land in Eglon influenced your connection to nature in general?

JP I started loving the land at an early age in DC, and I tried to get out as much as possible. I played little league baseball for a couple of years, just so that I could be on dirt for a while every week. I moved to West Virginia after eighth grade, and my friends in high school taught me what it was like to really grow up here—where everyone is in community with each other and the land. When I first got here, the land was something I had a connection to. It was a release and an escape, but I only saw it as property, a thing you have. What I came to realize is that the land here dictates a lifestyle, and at the same time, it’s your partner.

My mother had bought our land recently, and before we got there, it belonged to somebody else. If you live next to a river, you can’t control any part of it; when there’s high tide after snowmelt or heavy rain, the river is going to destroy lots of things that you don’t want to be destroyed. But the river also provides the subtle sounds that you love, good fish, clean water. It provides fertile land next to you, recreation, and peacefulness. I had to consume the land, through my eyes, nose, and ears, to understand that. I learned to coexist with the land.

“I had to consume the land, through my eyes, nose, and ears, to understand that. I learned to coexist with the land.” JP Castells

Earth In color What would you want to both archive for yourselves, and also pass on and inspire in other people?

JP live in fostering a genuine curiosity. When I was a kid, I asked “Why?” all the time. I went to parks and played with grass and used my imagination. Those things should be encouraged. I understand that not everybody has the opportunity to visit rural places like this, especially while living in a big city where it’s expensive to live, let alone travel. Still, I believe that every place presents an opportunity to try and be yourself, and if that means that you want to stay where you are and make your culture from the ground up from what you have, then you should. If you have children, or nephews, nieces, younger cousins—young people in general—around you, you should encourage them to go outside and ask questions: “What would make me feel good today?”

Ms. Sheila In many ways, you have to take risks. I could have truly screwed up my economic and social life by coming here because, although I have excellent skills, I didn’t know if they would be wanted here. But I kept saying, “I want a better life for my children.” Black people have done that in past generations, as migrants. We’ve got to keep sacrificing and diversifying ourselves to make sure that the next generation does not feel as trapped in cities or removed from the land. We have to ask ourselves: What do we need to make the next generation’s lives better?

“We have to ask ourselves: What do we need to make the next generation’s lives better?”

Ms. Sheila Castells

On the day this interview was conducted, May 30, 2020, it marked 14 years to the day that Ms. Sheila closed on The Holy Mountain.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)