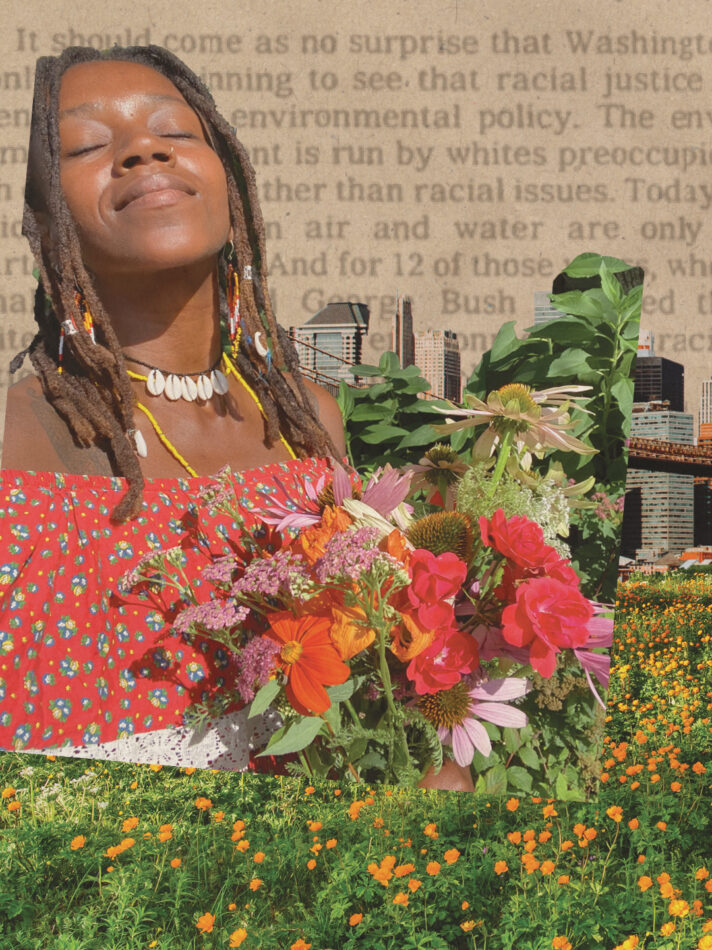

The Community Spotlight series highlights Black individuals and entities who are creating healthy, sustainable, and just futures. In this story, we feature Demetri Broxton, an Oakland-based artist and parent to over 200 houseplants. In this piece, Demetri shares his ongoing journey to becoming a plant expert, the connections between colonialism and houseplants, and the growing online Black houseplant community.

Growing up in the Bay Area, I have been surrounded by nature my entire life. Although I lived in East Oakland, my childhood home had a large backyard where my parents always maintained a gorgeous flower garden. My house was only four or five blocks from Mills College, so I would walk over there and hang out among the trees. We didn’t have a ton of money—often we were poor—but my parents had a good friend who owned a cabin in South Lake Tahoe. Family vacations were 90 percent going to the cabin and spending time on the lake and playing among the pine trees. These experiences gave me a very early appreciation for nature and helped me develop a desire to preserve, conserve, and protect the environment.

As an adult, I love going on hikes. Living in the Bay Area gives us incredible access to such a diverse array of natural areas. It’s nerdy, but one of my favorite things to do on hikes is look for “new-to-me” native species of plants. Last year, I learned about Trillium flowers. There’s a giant version that only grows in Northern California, Oregon, and Washington. I started searching online to learn more about where they naturally grow and discovered they like hillsides, shaded by Oak and other local trees. They often thrive beneath old-growth trees where the air is slightly cooler. So I began a search until last spring, when I found a cluster of them growing in the Berkeley hills. It’s a large and beautiful flower, but it’s also very delicate. If you pick the flowers, the entire plant is most likely going to die. So, you can really only enjoy them in their natural environment. I would take daily pilgrimages to visit the flowers. There’s something spiritual about being in their natural habitat. I love going out in nature and noticing the differences in the light and wind conditions—sometimes I even encounter wildlife. Something about being out in nature makes me feel more positive about my life.

Something about being out in nature makes me feel more positive about my life.

My mother always kept our home filled with houseplants. She was born and raised in Louisiana, but her family moved to Oakland when she was twelve. One of her neighbors gave her a cutting of Dieffenbachia (Dumb Cane) before the family packed up their car for the long trip to California. My mom was able to successfully root the cutting and over the years, one plant became several new plants that filled our house. Dieffenbachia can grow as tall as ten feet, but we had standard eight-foot ceilings. So she would cut the tops of the plants and root them to make more. When I was twelve, my mom taught me how to cut the Dieffenbachia and propagate them. I still have that original plant and several of its offspring, so one could say I began collecting plants at the age of twelve!

However, I didn’t get deep into collecting houseplants until 2019. Prior to that time, I had maybe thirty plants total in my house. Today, I have somewhere around 200 plants. I stopped counting at 170! I attribute my interest in collecting houseplants to the houseplant influencer and celebrity, Hilton Carter. In 2019, I came across his book Wild At Home, which features rooms in his house that are completely filled with the most amazing plants. I mean wall-to-wall plants that make you truly feel like you’re in a jungle setting. That was a transformative experience for me because I had never seen a Black person, but especially a Black cisgender man, who so boldly proclaimed his love of collecting plants. Before Hilton, I kept quiet about my love of plants, thinking it wasn’t something that many Black people did, certainly not men under the age of fifty. If an older Black man is gardening and taking care of plants, no one thinks anything of it. In traditional Western viewpoints, taking care of plants is not seen as a masculine thing, but I think to counteract toxic masculinity you need things like that. Seeing someone like Hilton who does plant design in people’s homes is really impactful. In Hilton I saw a very cool, well-connected Black person, who is like, “Yes, I take care of lots of plants. Here’s why I got into it. Here’s how I started taking care of them. Here’s what you can do to also take care of them.” Seeing that gave me a lot of affirmation as a young Black man who was interested in plants. It made me realize that there’s an entire world of folks that are into this, and I don’t feel alone anymore.

Today, I have somewhere around 200 plants. I stopped counting at 170!

blackness and greenness: A complicated history

You really need to know where plants come from in order to best take care of them because you’re trying to replicate their native environment as much as possible. The two plants that were passed down to me from my mom, the Dracaena massangeana (Mass Cane) and the Dieffenbachia (Dumb Cane) both originated in West Africa, the Senegambia region in particular. So, I began research to find out more about who went into that region to bring those plants outside of their native environment. There’s a direct parallel with Portuguese exploration in West Africa and collecting those plants to bring them back and put them in glass houses in Europe. Research shows that those initial trade routes ended up being the trade routes that directly connect to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. As I looked at those connections, I started to think broader about plants and imperialism.

Kew Gardens in England is a really ancient garden and you can look on their site to research plants and go all the way back to the archaeobotany of the plant. Oftentimes, the scientific name of a plant is named after the person who “discovered” it, which is saying a European person “found it” for the first time and brought it back to Europe. But when you start to look at those expeditions, they really tie in very closely with the imperial projects around the world. Going back to my own ancestry and looking at West Africa, plants were often the first things that were collected before people and resources, and then ultimately colonization of the land took place.

People who really get deeply into plants, especially rare plants, start to realize that this whole history of imperialism has basically exploited natural environments. But taking care of plants is not a new thing for people of color. It’s something that I’ve done my entire life. In conversations that I’ve had with other BIPOC plant owners, we’ve talked about how it’s natural for people of color, particularly Black people, to care for plants. We did it before enslavement, we did it during enslavement, and we did it after enslavement. The knowledge of how to care for plants is in our blood. Today, Black people mostly live in urban environments, for many reasons. Particularly after the Great Migration, we got removed from environments where we had deeper connections to the Earth, but many of the houseplants we now care for come from the lands of our native ancestors—so there is this natural connection. I am particularly into calling out plants that come from Africa. A lot of us don’t realize that some of these really incredible, highly-sought after plants that are now worth tons of money actually come from the same place as our ancestors.

But taking care of plants is not a new thing for people of color. It’s something that I’ve done my entire life.

cultivating community online

As I learned more about plants, I discovered plant communities that consisted of mostly White people. So every time I would find a Black person who was into plants, I’d follow them, we’d start a conversation, and then we’d start to trade. Social media can be so incredible for building a community of like-minded folks. For me and for so many folks, we were taking care of plants, but it wasn’t cool or something you really talked about. Within the last decade, because of social media, we’ve found out that there’s other people like us. Instagram is my favorite way to meet plant friends, and I have a small group of plant friends located in South Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, Greece, and the United States that I have developed deep and lasting relationships with. These virtual friends, most of whom I haven’t met in real life yet, stay in touch with me and check in on my well-being on a weekly and sometimes daily basis.

We give each other plant advice, lift each other through rough times, and even tell each other about great prices for rare plants. As I’ve built my plant collection, I’ve gotten some really rare plants that are worth ridiculous amounts of money, but I just collected them because of my love for them. So I’ve been giving them to Black plant friends, and those same friends have sent me plants in return. For example, in 2020 one of my Instagram friends told me about twenty dollar Variegated Monstera nodes. These same plants have grown into huge, beautiful plants that are now easily worth one hundred times what I paid—but more importantly than helping me find a plug on rare plants, these folks genuinely care that I’m doing well. We’ve built this relationship, so it’s not just about the money or the exchange. The entry into these relationships is about plants, but then we check in with each other to see how we’re doing and have deeper conversations. I think plants, just like any other thing that people get obsessed with, serve as the entrypoint for conversation. There’s also something nurturing about plants and being a plant parent, so we want to bring that same level of nurturing and care to each other. We all see plant care as self-care. We are devoted to the practice of learning to provide our plants with the precise care that will allow them to thrive, but we also care to see each other thrive. And because I’ve made a ton of international plant friends, my next goal is to actually connect with those people in real life. I want to see these plants in their native environments and travel to all of these beautiful tropical regions that have Black and brown folks.

growing a safe space

Plants have always brought me joy and peace. The ability to nurture any living organism and see your efforts have a direct impact is probably what I most love about being a plant parent. Not many things in life have that same level of feedback, where whatever you put out, shows an equivalent return. Furthermore, I love the challenge of figuring out the various care needs of different plants. When a person becomes a brand new plant parent, the biggest mistake I see is usually overwatering plants. You quickly learn that plants like cacti and succulents generally want to be left alone. If you water them too frequently, you overwhelm their root system and they rot. On the opposite end of the spectrum are Calatheas, which need constant watering and humidity. I find joy in learning the needs of my various plants and providing exactly the right conditions for them to thrive. My daily and weekly routines with my plants bring me a sense of calm. It’s meditative and allows me quiet time to contemplate the things I need in my life in order to thrive. There’s really a connection between mental health and also a spiritual well-being that taking care of houseplants can bring.

Now there are definitely limitations. If you have too many plants, then it’s not peaceful or relaxing! But if you find that right balance of plants, you start to just learn so much about yourself. At that point, it’s not even a hobby, it turns into a total lifestyle. A lot of folks that I’m friends with suffer from depression and they find healing from taking care of houseplants. There’s this idea that if I learn what this plant needs, and I provide it with what it needs, it’s going to thrive, and in turn it’s going to make me feel good about myself.

My daily and weekly routines with my plants bring me a sense of calm. It’s meditative and allows me quiet time to contemplate the things I need in my life in order to thrive.

Demetri Broxton lives in Oakland, CA and has been caring for indoor plants since childhood. He is now the owner of over two hundred houseplants. He chronicles his plant journey on his Instagram account, @the_botanical_blasian. To support his plant habit, Demetri works as the Senior Director of Education at Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, CA and is a practicing visual artist represented by Patricia Sweetow Gallery.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)