Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

Bees have historically served as symbols of dedication and hard work and cultures throughout time have enjoyed their honey as a delicious form of liquid gold. Though modern species of honeybees aren’t native to North America, bees have played an integral role in the reproduction cycles of plants around the world. Beekeeping, honey, and bees even have a long history in African and African American culture that is not widely documented. Today, beekeeping practices are growing in popularity among young Black folks who are looking to reconnect with nature and produce their own honey.

the science of healthy hives

Have you ever sniffed a rose only to find a bee staring back at you? Perhaps you’ve noticed honeybees drunk on nectar, floating between flower buds in summer. The honeybee is a marvel. A single bee may look small, but she is a part of a much larger collective consciousness, a super-organism of diligent worker bees that unintentionally keep nature healthy and thriving. True bees—not yellow jackets, which are actually members of the wasp family—are famous for flitting between flower beds, collecting the yellow pollen until their nectar sacs are full, and returning to their hive to turn it into food for themselves and the thousands of babies their queen produces each day. A healthy colony can hold as many as 80,000 bees in the summer season when warmer temperatures and blooming flowers ensure that there’s enough food for the queen to lay an egg every twenty seconds. These eggs are housed in the center of the hive with the queen until they hatch into worker bees that go out to collect nectar. The queen uses pheromones to keep her workers in line; the bees out collecting pollen will follow that pheromone trail to find their way back to the hive with their nectar sacs full of honey-making powder. The honey we love is produced when collected nectar is passed from bee to bee, mouth-to-mouth, before it is stored in the hexagonal holes of the hive walls.

Honey bees alone account for about 80 percent of pollination in flowering plants, including many fruits and vegetables.

Although the bees’ reason for collecting nectar is pure self-preservation, their flower flitting is actually pollinating the flowers and plants. Individual bees will only draw pollen from a single flower species in its life—so when a fledgling bee leaves the hive for the first time, the first flower species it finds will be the species it visits for the rest of its lifetime. This floral fidelity makes honeybees some of the best pollinators; the pollen that is inevitably caught on the bees’ fuzz receives a free ride between flowers, ensuring that flowers, shrubs, fruit, and trees, can reproduce. Honeybees alone account for about 80 percent of pollination in flowering plants, including many fruits and vegetables. About one-third of the food we eat is affected by bee populations, so much so that millions of dollars are spent every year renting hives that both pollinate crops and contribute to a rather profitable honey industry. Unfortunately, climate change is contributing to temperature shifts and habitat loss that is restricting the range of bee populations worldwide. Rising monthly temperatures are causing earlier flowering seasons and leading to mismatches in seasonal timing between bees and the flowers they rely on. As the bees’ inhabitable territories shrink, bee populations are declining by about 40 percent each year.

This is where beekeeping comes in. Beekeepers—also called apiarists—help keep bees alive and support pollination by maintaining bee shelters and providing medicines and other care to ensure the colony doesn’t lose its queen or grow weak in the winter. To be clear, beekeeping is not as simple as setting up a hive and letting the bees do their thing. If left to their own devices, domesticated bees used for beekeeping may not collect enough food to sustain themselves during the cold months and they can also become disease-ridden or fall victim to local predators like bears, birds, and hive beetles.. A beekeeper’s job is to monitor the bees, supplement food where necessary, and ensure the bees can roam freely and with enough local flora to produce plenty of honey for winter. This is how beekeepers also contribute to the pollination process.

black beekeeping

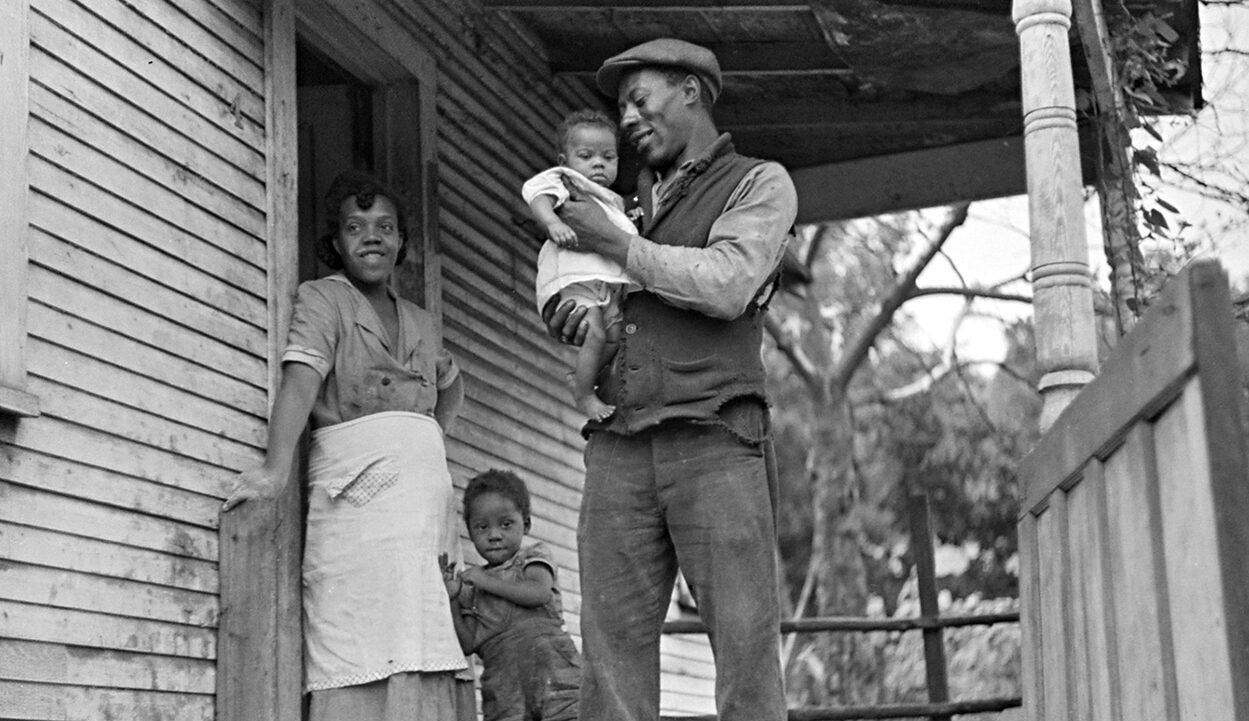

There is a long history of Black beekeeping traditions in the United States, but prior to the 1890s much of that tradition and knowledge was only kept sparingly and lost over time. That is before the Tuskegee Institute added beekeeping to their curriculum as an important agrarian skill for Black men and women. Although Tuskegee instructors like George Washington Carver and Dr. Booker T. Whatley served as staunch advocates for beekeeping education among Black farmers, one of the most famous Tuskegee bee enthusiasts was Margaret Murray Washington, who founded The Lady Beekeeper club in 1892. As Booker T. Washington’s wife and Dean of Women at the Tuskegee Institute, Murray Washington promoted vocational education and practical skill building for women, instructing her students in sewing, canning, child care, literacy, and beekeeping with the thought that a well-rounded woman with a multitude of domestic skills could gain employment anywhere. Her beekeeping organization became one of the most highly regarded programs of the time. It was known for its membership of women who were so confident with bees that they were famous for not wearing veils. The depth of Murray Washington’s contributions to the beekeeping movement are not well-documented as is the connection between honey and the African diaspora. Snippets of this history have been collected together from narratives by enslaved Africans, oral history, and a few famous images of the Lady Beekeepers in Tuskegee.

Regardless of the missing history, the art of beekeeping has grown to prominence in recent years as the burgeoning Black beekeeping community works to preserve declining bee populations and reclaim connections to land, food, and nature.

Perhaps most famously, First Lady Michelle Obama set up a beehive at the White House back in 2009. And beekeepers like the Johnsons of Zach and Zoe’s Sweet Bee Farm and urban beekeepers like Nicole Lindsay and Timothy Paule Jackson of Detroit Hives are among the many Black nature enthusiasts attempting to combat these stereotypes and replicate the practices developed by Black beekeepers at the Tuskegee Institute.

You may recognize the Johnsons from a 2021 episode of Shark Tank, where they pitched their homegrown raw honey and superfood blends. Kam, Summer, Zach, and Zoe Johnson built their business after discovering the power raw honey had to relieve Zach’s severe asthma attacks and seasonal allergies. The family also uses their seven acres of rural New Jersey landscape as a source of hands-on, experiential learning and an opportunity for their children to connect to nature—a replication of the sort of hard skill-building that the agri-enthusiasts of the Tuskegee Institute developed centuries ago.

Beekeeping is not exclusive to rural farmers; Detroit Hives was founded as a source of education, conservation, and honey in the urban centers of Michigan. Timothy and Nicole created the now expansive beekeeping organization to reconnect themselves to the healing power of nature and raw honey. They have since founded National Urban Beekeeping Day on July 19th and transformed their operation from a single beehive into a youth education and nature appreciating facility with forty-three individual bee colonies and close to 2.5 million honeybees.

Beekeepers in Atlanta, North Carolina, and nationwide are attempting to educate all people, in urban and rural places alike, about the power of bees, the potential health benefits of local raw honey, and the peace that comes with caring for the collective. They draw their inspiration from the educators and farmers before them and from the healing, collective nature of the bees themselves.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)