Welcome to Earth Curiosity, a series that uncovers overlooked connections between science, innovation, nature, and our community. Dive into all the ways Black people have been innovating, sustaining, and thriving through our connections to and deep knowledge of the natural world both past and present.

Every breath you take can be attributed to the tree tops and forest ecosystems that cover this planet. Forests are the literal lungs of the Earth—a community of interconnected, constantly communicating trees, shrubs, and fungi that contain some of the most biodiverse ecosystem types in the world. From the deciduous oak, maple, and birch forests of the temperate regions in the American Southeast to the coniferous pine, spruce, and fir treescapes of the Northwest, forests provide us innumerable services. They create air for us, hold the soil together, combat the causes and symptoms of climate change, as well as house the large and small animals that keep our planet healthy and beautiful.

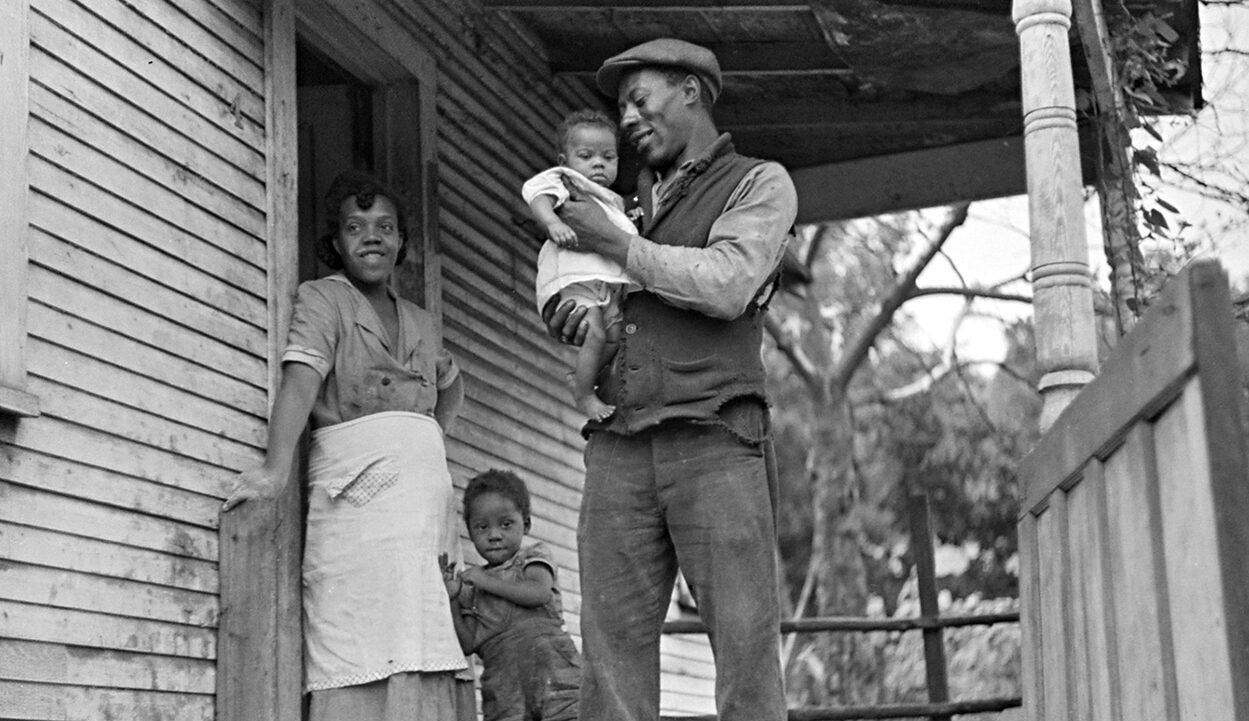

Despite the diversity and ubiquity of forests in the US, access to these critical resources has not been equal. Entities like the US Forest Service were founded and grounded in harmful assumptions about the relationship—or lack thereof—between Black folks and nature. But that is changing. We are returning to the outdoors, to nature, to our tree spaces. As a people, we are reclaiming our forests.

more than a couple of trees

If you’ve ever seen the carnage of the forest floor after a brush fire, you have a sense of just how resilient our forest ecosystems are. Not even a couple of days later, bright green spouts of new life pop up between the dead leaves and ash. A couple of weeks after that, you have a new mini forest growing in the gaps between old-growth trees. Forests cover approximately thirty percent of the globe and reside on every continent except Antarctica. They are wide-ranging with looks and function that vary vastly across the United States. Even though they differ in appearance and function, they all serve similar and extremely important ecological functions.

Forests, especially old-growth forests are an important carbon sink, a massive collection of different photosynthesizing plants that take in and store carbon dioxide to produce the oxygen we breathe. This carbon extraction also works for other types of pollution; these ecosystems suck up compounds like nitrogen dioxide or ground-level ozone, which have been linked to acid rain and smog, and replace them with breathable oxygen. There’s a reason why forests are called the lungs of the Earth.

These collections of trees also do marvelous things for the soil. Their deep root systems help hold loose gravel and organic matter together, limiting key soil nutrients from escaping during heavy rains and preventing major flooding during severe weather events. It’s not uncommon for communities to experience previously unheard of flash flooding after a swath of trees or forest is clear-cut in the area.

That’s right, trees talk to each other. Using networks of fungi under the soil, trees can communicate their needs and potential threats to each other almost instantly.

And perhaps most significant is the role of forests as a habitat for a multitude of animal beings. A tree can be a very giving partner for forest critters. The squirrels find their food and birds build their homes in the tree branches, insects take refuge inside the bark, and larger creatures like deer, rabbits, and hedgehogs, take shelter amongst the roots. A tree also provides food in the form of fruit, nuts, flowers, and more. The older the forest, the more biodiverse it is. An older forest’s biodiversity can look like fungi spreading across tree roots, butterflies and hummingbirds flitting between branches, and vines and ivy taking advantage of forest structures to climb up toward the sunlight.

One fascinating feature of these woody ecosystems is their cohesion. When describing the benefits of trees to the air, soil, and other creatures, it is not a description of any lone tree. It is the collection of trees, the forest as a whole that works to our benefit. One tree can only pull so much pollution from the air, but a forest makes a proper carbon sink. One set of roots can only do so much for the soil, but when the roots of the collective are working together, they create a strong foundation for the earth around them. And the trees that make up a forest aren’t just operating randomly; they are living organisms that communicate with each other.

That’s right, trees talk to each other. Using networks of fungi under the soil, trees can communicate their needs and potential threats to each other almost instantly. These fungi-tree underground partnerships are commonly called mycorrhizal. Thin strands of fungi cover and fuse with tree roots allowing trees to pass resources like water between each other, sometimes for no other reason than the tree’s generosity. This relationship is mutually beneficial for the fungi and trees involved. The fungi help trees collect water and nutrients from the soil in exchange for food that the tree makes during photosynthesis. These networks have the added benefit of connecting trees and plants in a forest together, a game of telephone that can stretch for miles across a forest scape. The scientist who discovered this phenomenon has described this relationship between trees in a forest as “a vast, ancient, and intricate society,” a community of individual trees that operates in tandem with the other plants and trees around them to negotiate and interact peacefully. This concept of communication gives a whole new meaning to the benefits of forest ecosystems. These are organisms working with intention, an efficient system fulfilling a multitude of purposes.

It’s estimated that approximately 57 percent of the world’s land was covered by forests 10,000 years ago. Deforestation, the destruction of forests for timber or to use the land for agriculture, has drastically reduced and fragmented forest coverage. Fortunately, forests have a fascinating superpower in the form of succession. This is the process that sprouts baby forests after a bush fire decimates the landscape. This process of new growth and regrowth may seem slow through human eyes, but it is actually a fast-paced show of forest resilience. What was once barren land can be transformed into vast woody stretches in a matter of decades.

The US Forest Service was created with succession and the preservation of these woodland “societies” in mind.

a fraught forest history

The US Forest Service was created in 1905 to protect and preserve the country’s natural forest resources for their ecological benefit as well as their aesthetic value. However, the service is not without its drawbacks. One of its original mandates allowed the US to sustainably harvest our natural forest systems (so it was less about conservation and more about making money). This practice was ingrained in the foundation of the Forest Service, as well as the National Park Service, and has a history of racism.

The first head of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, often referred to as the Father of Forestry was also a member of the International Eugenics Congress, an organization and movement focused on the sterilization of people of color and differently abled individuals. The founding of the Forest Service occurred in tandem with the development of the environmental movement when officials like Theodore Roosevelt gave power to people like Gifford Pinchot and John Muir who viewed the outdoors as a respite for wealthy White people.

The growing racist and classist view of natural systems for leisure as well as the view of natural resources as commodities led to the systematic physical and social exclusion of Black people from outdoor spaces. This, combined with cultural insensitivity in the naming of national forests, parks and monuments along with the segregation of public lands has reduced Black people’s access to the national forest system. Studies have shown that even though 35.5 percent of people of color live within fifty miles of a national forest, these forests only see about 11.7 percent of visitors of color each year. And Black people only made up about 1 percent of national forest visits.

Melody Mobley is one of the most notable Black Forest Service representatives in US history. She was the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Washington with a degree in forest management, and she was the first professional Black woman forester to serve in the US Forest Service. Mobley has spoken openly about the racism, sexual assault, and discrimination she experienced, and oftentimes buried while moving her way up in the Forest Service. In an excerpt from a personal essay titled A Black Woman Who Tried to Survive in the Dark, White Forest, she wrote, “I have heard it stated that ‘Black people don’t go into the forest.” But for her, nature was home. And despite several instances of physical violence and verbal assault, Mobley built a life and a name for herself in the Forest Service, one that now translates to diversity, equity, and inclusion work within the environmental movement as a whole.

Studies have shown that even though 35.5 percent of people of color live within fifty miles of a national forest, these forests only see about 11.7 percent of visitors of color each year.

There’s still a long way to go. Mobley said that in 2017 the number of Black women foresters in the field increased from zero to six since she joined in 1977, but Mobley has continued her passion for forest conservation and education by working with young children of color to teach them about nature and environmental management. She believes that one of the most important and missing pieces in increasing representation in public lands and national forests is in youth education—getting kids outdoors and appreciating the ecology of forest ecosystems. She has become a face for Black folks in forests and Black folks in nature. In the summer of 2021, the US Forest Service named its first Black chief, Randy Moore, in its then 116-year history—an action that Mobley has praised as a critical step toward representation in the great outdoors.

Forest ecosystems, their uncanny ability to communicate with each other, and the health benefits they provide are a public good. And whether it’s Black birders, hikers, or foresters like Melody Mobley, there are a lot of Black people reclaiming the forests for our community, inside and outside the Forest Service.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)