This story was originally published in the first issue of Radicle, our interactive print publication which centers Black voices and perspectives in sustainability and the environment. Radicle explores a range of topics including environmental justice, indigeneity, sustainable homebuilding, and plant-forward home cooking. The publication was designed to spark curiosity and celebrate community, all while healing our people and the planet.

When I hear the word “sustainable,” I think of the color green—a vague, self-sustaining paradise. Reduce. Reuse. Recycle. Paper instead of plastic. But what happens when you apply the principles of sustainability to homebuilding—or the process of furnishing and decorating your home?

It’s easy to think of sustainable homebuilding as a luxury, a consideration only for those with the time and resources (read: money) to invest in a “green” lifestyle. Modern sustainability movements often encourage sustainable practices without cultural or historical context, alienating our communities and erasing our narratives. But sustainability is inherently inclusive—a way of living and thinking that is adaptable to every way of life.

If you look around your space right now, there are probably at least a few pieces that have been handed down or adapted from other places. Your grandmother’s quilt on the back of the couch? The bed frame you bought on Craigslist rather than new from IKEA? That’s sustainable homebuilding, which is often subconscious. All it means is that an effort has been made to reuse rather than consume, and contribute rather than take.

That’s sustainable homebuilding, which is often subconscious. All it means is that an effort has been made to reuse rather than consume, and contribute rather than take.

I consider homebuilding a hobby I inadvertently picked up from my mom over the years, a form of self-expression, an opportunity to let people know who I am without having to tell them anything. When I moved to the Bay Area nearly a year ago, it felt like the beginning of a new adventure, my first steps toward both imagining and creating the kind of life I might want for myself. I was in the midst of a career pivot, and had left my home state of Texas to be roommates with my brother, a recent graduate of Stanford’s engineering school, who was also embarking on his own life transition from college into the real world. Unlike my brother though, who had spent the last four years sharing a dorm room, I had been out of school for a couple of years, and in that time had grown accustomed to living alone and to a certain degree of quality. I didn’t have a lot of disposable income to furnish an apartment, but I knew that the things I did buy I wanted to last.

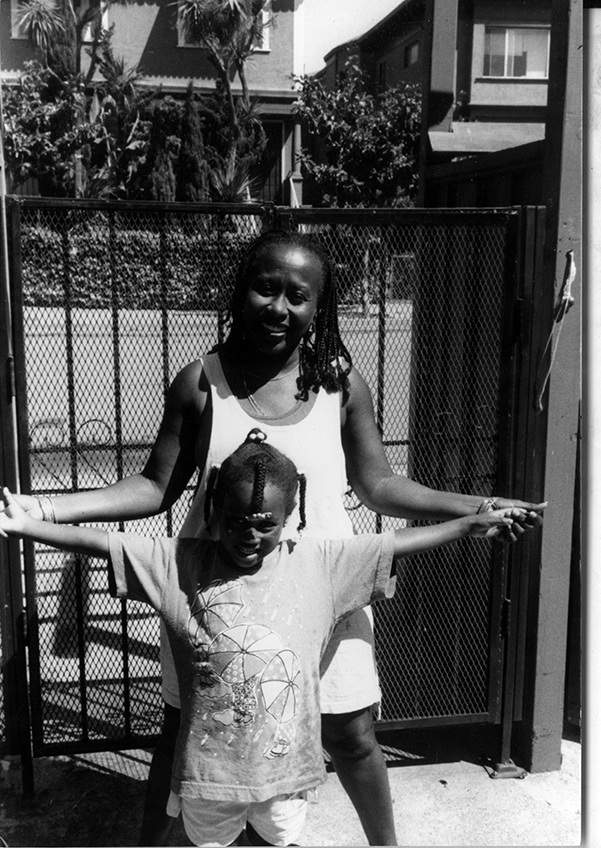

Before moving to the Bay Area, I had never considered yard sales as hotbeds of sustainable activity. I did have some experience with yard sales, though. Nearly every Saturday morning growing up, my brother and I would load into my grandmother’s big white van, with the silvery gray streak down the side, and the three of us would cruise the neighborhood looking for yard sales. When we rolled across one that looked promising, my grandmother would pull the van to a stop, often in the middle of the street, and my brother and I would hop out and run to take a look at the sale’s offerings. We were never looking for anything in particular, really just anything interesting, handy, or useful—a lamp with a clear glass nodule for holding gasoline, a bright red T-shirt with a picture of Lightning McQueen, a plastic pink Barbie dream house, taller than my waist, and enshrined in a fine layer of dust.

When we found something interesting we would ask our neighbor for the object’s price, then hurry back to the van to report our findings. My grandmother would deliberate like a sentinel, often sending us back and forth to haggle before we finally trotted back toward the van, cash dispensed, and arms laden with our spoils. I never would have guessed that those weekend yard sale trips, scouring for gems and haggling for bargains, were preparing me to be a transplant in a new city over a decade later, or how my grandmother’s shrewd eye, and the value she placed on other people’s belongings, would inform my own ideas about sustainability and environmentally conscious homebuilding.

Drive through Oakland or Berkeley on a weekend in mid-June, and you’ll find a yard sale on seemingly every corner. I had learned from weekends with my grandmother the great finds to be had at yard sales and how to be intentional about finding quality pieces while being firm but fair about prices. As a transplant in the Bay Area, I decided to use the yard sales as an opportunity to furnish our new home, while learning more about our new neighborhood and neighbors. As weekends with my grandmother taught me, a lot can be learned about someone by the objects they give or throw away.

As weekends with my grandmother taught me, a lot can be learned about someone by the objects they give or throw away.

There are different ways to scope out yard sales. My brother is a Craigslist aficionado, and for those interested in a more organized approach, a tiny bit of research goes a long way. It’s not uncommon for people to post the items they plan to unload online before arranging them in their front yards. Together, my brother and I developed a spreadsheet—complete with addresses, prices, and the furnishings we hoped to cop at each stop. On our travels we also fell into a fair number of sales by accident, taking detours from our carefully researched routes to check out flyers affixed to telephone poles, and following meandering directions down side streets to whatever treasures laid at their ends.

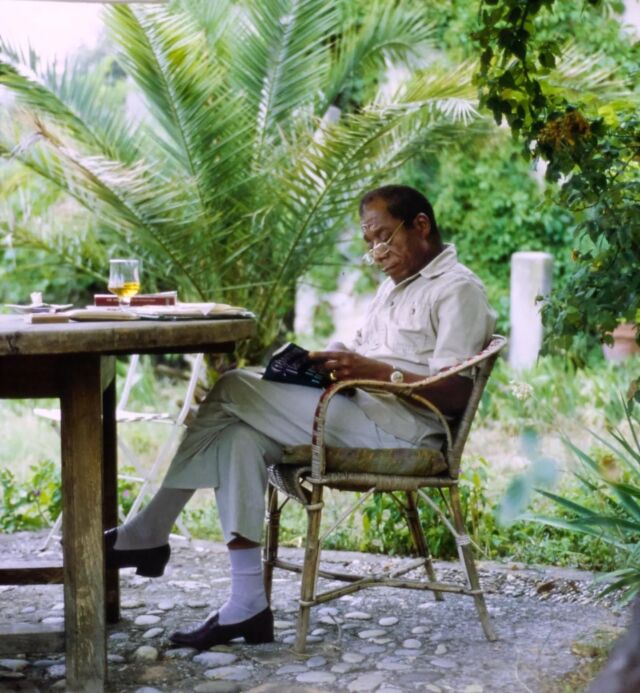

Occasionally between destinations, we’d spot something particularly interesting, and I’d bring the car to a jarring halt, much as my grandmother had when we were younger, hitting the hazards and hopping out to grab a rare find left in the grassy median between the sidewalk and the street (the mirror in my room, an old door reoutfitted with reflective glass in lieu of windowpanes, was one of these rare finds, as well as most of the chairs in our apartment). Our most successful yard sale was one of these rare accidental finds. Following a pole sign to an estate sale buried deep within the Berkeley hills, we stumbled upon the home of a former New York Times journalist who was leaving the country—in what struck me as kind of a hurry—to spend an indeterminate amount of time with his wife and two elementary school-aged children at sea. (The whole scene was pretty sketchy, and in today’s America, who knows what that man stumbled onto or was running from).

Our most successful yard sale was one of these rare accidental finds.

We cleaned up that day—getting the bed frame in the master bedroom, black with an expansive headboard—which went perfectly with the mattress we’d gotten, still new in its plastic, from a friend of a friend’s aunt who happened to be clearing space in her storage, in one of those kismet things the universe does sometimes—a beige couch with cushions that sank when we sat down; a beautiful glass-topped drafting table; and other odds and ends, like the bright red barstool that I wanted implicitly, despite no bar anywhere in our apartment to speak of—all for less than $200. This was not the originally quoted price, but as the day wore on and the family realized they wouldn’t be able to sell all their pieces, they called us, remembering the three Black kids (me, my brother, and our cousin who had flown up from Texas to help us move) who had pulled up to their sale earlier that day and balked at the prices listed before apologetically driving away.

“Did we say $150 for the couch?” the husband/father/New York Times journalist had said when he’d called us later that evening. “We meant $150 for everything.” Within an hour we were back at their place, followed by a good family friend who’d borrowed her uncle’s station wagon to help us load up. As their two kids played on a rug in their front yard, we walked in and out of their home, taking basically anything that looked remotely interesting, his wife all the while adding more things to our pile. “Good luck,” he’d said, shaking our hands before we drove away.

By the end of the summer, my brother and I had furnished our entire home for less than $500, with quality pieces we were happy to have in our apartment rather than collecting dust in someone’s garage, or languishing in a landfill. More than just furnishing our apartment though, we had learned about our community, getting comfortable with our neighbors and neighborhood in a way we only could by spending hours combing the streets.

The whole experience was empowering. We had more agency over the shaping of our space than we had previously realized. We had repurposed the objects others had tended to sustain ourselves. We were making an effort to reuse rather than consume, to contribute and not simply take. We were thinking of ourselves in the context of our neighborhood, our environment. And in doing so, we had sustainably built our home. Sustainability doesn’t mean difficult, or expensive, or exclusionary. And with a few minor mental adjustments, and the right idea of where to look, you’ll find that sustainability actually comes naturally.

We were thinking of ourselves in the context of our neighborhood, our environment. And in doing so, we had sustainably built our home.

![Did you know you could be buying fake honey? 👀🍯

According to @detroithives co-founder Timothy Paule Jackson, “ninety percent of most honey that you get in big box stores is fake.” To make sure you’re getting the real stuff, he suggests checking out the nutrition label. Fake honey will have ingredients like “high fructose corn syrup, peach syrup, [and] it’ll have some type of sugar.” Avoid honey labeled as “pure” or “pasteurized,” and instead look for words like “raw” or “local.”

And with winter approaching, it’s the perfect time to stock up — not only is it full of vitamins and minerals, but real honey can also be used as a remedy for sore throats and coughs. Swipe to check out some of our favorite Black-owned bee farms and Black beekeepers selling the good stuff 🐝🍯](https://earthincolor.co/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/314552686_126502226881255_7598404171432106028_nfull.jpg)